עוד בעניין תערו של אוקהאם

בס”ד

בד’ד – תשע”ב

מיכאל אברהם

ר”מ וראש בית המדרש לדוקטורנטיות מצטיינות, המכון הגבוה לתורה, אוני’ בר אילן

כתובת בבית: גליצנשטיין 5/4 פתח תקווה, 49559.

טלפון: 03-9170387

נייד: 052-3320543

דוא”ל: mikyab@gmail.com

תקציר

מאמר זה נכתב בעקבות מאמרו של מתן בנימין, שהשווה בין החובה לדון לכף זכות לבין פרשנות לפי עקרון התער של אוקהאם. בשני המקרים מדובר לדעתו בפרשנות שמטרתה אינה האמת, אלא מטרה ערכית או אסתטית.

במאמר זה אני חולק על שתי הקביעות העיקריות שלו, וממילא גם על המסקנה: החובה לדון לכף זכות אינה דורשת סטייה מהאמת העובדתית. כמו כן, התער של אוקהאם הוא אמצעי להגיע לאמת (ולא רק עיקרון אסתטי). בגלל שהטעות ביחס לעקרון התער מאוד נפוצה אני מצרף נספח ובו הוכחה לגישתי.

Michael Abraham

R”M and head of Beit Midrash for outstanding doctoral students, High Torah Institute, Bar-Ilan university

Private adress: Glicenstein 5/4, Petah Tiqva, 49559, Israel

Tel: 03-9170387

Cell phone: 052-3320543

E-mail: mikyab@gmail.com

Abstract

This article concerns Matan Binyamin’s article in which he claimed that our Halakhic duty to make allowance (LADUN LEKAF ZEKHUT) is similar to the use of Okham’s razor, because they both don’t aim to the factual truth.

In this article I show why I disagree with the two claims, and in the appendix I offer a proof to my interpretation for Okham’s principle.

עוד בעניין תערו של אוקהאם

מבוא

מתן בנימין, במאמרו בגיליון 24 ערך השוואה בין עקרון התער של אוקהאם לבין הדרישה לדון לכף זכות. בשני המקרים, הוא טוען, מדובר על פרשנות שאינה תואמת את העובדות לאשורן (‘אמת אונטולוגית’, בלשונו), אלא נעשית משיקולים אחרים ונבחנת לפי פרמטרים אחרים (‘אמת קיומית’, בלשונו).

ניתן לתמצת את טיעונו באופן הבא:

- הדרישה לדון לכף זכות אינה מיועדת להגיע לאמת העובדתית אלא להגיע לתמונת עולם קוהרנטית (באופן שאינו סותר בהכרח את העובדות), כדי שהאדם אותו אנו שופטים יצא נקי ככל האפשר. הפרשנות יכולה להיות רחוקה מהשכל הישר, ובעלת סבירות נמוכה מאוד, והיא נמדדת במונחים מוסריים ולא עובדתיים.

- גם תערו של אוקהאם שמשמש אותנו במדע ובכל תחומי החשיבה שלנו, הוא עיקרון פרשני שאינו שואף להגיע לאמת אלא לפשטות ונוחיות. כאן הוא מסתמך על ספרו של הוקינג קיצור תולדות הזמן, והוא מזכיר בהערה את מאמרי (שלא פורסם. ראה את ההוכחה כאן בנספח) בו הצגתי הוכחה נגד העמדה הזו.

- מתוך ההשוואה בין שני המקרים הללו, טוען מתן בנימין, כי במקרים מסויימים בהם האמת האונטולוגית אינה אפשרית, יש להעדיף את האמת הקיומית על זו האונטולוגית. נראה שכוונתו להסביר את ההיגיון בדרישה לדון לכף זכות (אמת קיומית על חשבון האונטולוגיה) באמצעות השימוש המדעי בתער של אוקהאם.

לצורך ערעור על המסקנה, די בערעור של אחד מרכיבי הטיעון. אולם כאן מצאתי את עצמי חולק על שלושתם כאחד. במאמר הקצר כאן אנסה להסביר מדוע, ולהציג תמונה אלטרנטיבית. העמדות שהוצגו במאמרו של בנימין מבוססות על הנחות רווחות מאד, ולכן יש חשיבות בבירור הסוגיה הזו, גם מעבר לויכוח על תזה ספציפית כזו או אחרת. בשלושת הסעיפים הבאים אתייחס לשלוש הנקודות דלעיל אחת לאחת.

א. הוי דן את כל האדם לכף זכות

הנקודה הראשונה בה אני חולק על בנימין היא הדרך בה פירש את החובה לדון לכף זכות. המשנה באבות (א, ו) קובעת:

יהושע בן פרחיה ונתאי הארבלי קבלו מהם יהושע בן פרחיה אומר עשה לך רב וקנה לך חבר והוי דן את כל האדם לכף זכות:

לדעתו של בנימין חובה זו דורשת מאיתנו לאמץ פרשנויות דחוקות לגבי המציאות, מסיבות מוסריות, גם כשאנחנו משוכנעים שהפרשנות הזו אינה נכונה. אמנם הוא מעיר שאין לאמץ פרשנויות בלתי אפשריות (כלומר כאלו שנסתרות חזיתית מכוח עובדות).

ניתן לצרף כאן את הסיפור הידוע על הגר”ח מבריסק ששאלו אותו: לכל דבר שנברא יש סיבה ותכלית. לשם מה, אם כן, נברא שכל עקום? הגר”ח ענה: כדי ללמד זכות. הנחתו של הגר”ח היא שלימוד זכות אמור להיעשות בשכל עקום.

כראיה לפירושו מביא בנימין מעשה המסופר במסכת שבת קכז ע”ב, שם אנחנו מוצאים מעשה בפועל שלא שולם לו שכרו. הפועל (שהפרשנים מזהים אותו עם ר”ע) מציע שם פרשנויות דחוקות מאוד שמצדיקות את המעסיק שלו, בניגוד לפרשנות המתבקשת שהוא פשוט רשע ומלין שכר.

אך הדברים נסתרים מפירושי הראשונים על המשנה במסכת אבות. לדוגמה, הרמב”ם על אתר כותב:

והוי דן את כל האדם לכף זכות – עניינו, שאם יהיה אדם שאינו ידוע לך, לא תדע האם צדיק הוא או רשע, ותראהו עושה מעשה או אומר דבר, שאם יפורש באופן מה הריהו טוב, ואם תפרשהו באופן אחר הרי הוא רע – פרשהו כטוב, ואל תחשוב בו רע. אבל אם היה איש ידוע שהוא צדיק, ומפורסם במעשי הטוב, ונראה לו מעשה שכל תכונותיו יורו על היותו מעשה רע, ואין להכריע בו שהוא מעשה טוב אלא בדוחק רב מאד ובאפשרות רחוקה – צריך לפרש אותו כטוב, הואיל ויש צד אפשרות להיותו טוב, ואין מותר לחושדו, ועל זה יאמרו: “כל החושד כשרים לוקה בגופו”. וכן אם היה רשע ונתפרסמו מעשיו, ואחר כך ראינוהו עושה מעשה שראיותיו כולן מורות שהוא טוב, ובו צד אפשרות רחוקה מאד לרע – צריך להשמר ממנו, ולא להאמין בו טוב, הואיל ויש בו אפשרות לרע, אמר: +משלי כו, כה+ “כי יחנן קולו אל תאמן בו, כי שבע תועבות בליבו”. ואם היה בלתי ידוע, והמעשה נוטה אל אחד משני הקצוות – צריך בדרך המעלה שידון לכף זכות, איזה משני הקצוות שתהיה.

הרמב”ם קובע שקיימת חובה לדון לכף זכות רק במקום ששתי האפשרויות באות בחשבון במידה שווה. אבל במקום בו לאור ההיכרות שלנו עם בעל המעשה מתבקשת פרשנות אחרת, שם אין לעקם את המציאות.

כך משמע גם מפירוש רבנו עובדיה מברטנורא שם, שכתב:

והוי דן את כל האדם לכף זכות – כשהדבר בכף מאזנים ואין לו הכרע לכאן ולכאן. כגון אדם שאין אנו יודעים ממעשיו אם צדיק אם רשע ועשה מעשה שאפשר לדונו לזכות ואפשר לדונו לחובה, מדת חסידות היא לדונו לכף זכות. אבל אדם שהוחזק ברשע, מותר לדונו לחובה, שלא אמרו אלא החושד בכשרים לוקה בגופו [שבת צ”ז א], מכלל שהחושד ברשעים אינו לוקה:

רבנו יונה בפירושו שם מאריך בדבר, וכותב דברים דומים:

והוי דן את כל האדם לכף זכות. זה מדבר עם אדם שאין יודעין בו אם הוא צדיק ואם הוא רשע. ואם מכירים אותו והוא איש בינוני פעמים עושה רע ופעמים עושה טוב ואם יעשה דבר שיש לדונו לכף חובה ויש לדונו לזכות בשיקול או אפילו לפי הנראה נוטה לכף חובה יותר, אם משום צד יכול לדונו לזכות יש לו לומר לטובה נתכוון. אבל אין הדברים בצדיק גמור ולא ברשע גמור…

הוא מדבר בפירוש על חובה לדון לכף זכות רק במקום בו שני הצדדים הם בשיקול (=בעלי משקל דומה), או לכל היותר כשיש נטייה קלה לטובת הצד השלילי (שהרי לכל אדם יש חזקת כשרות). אבל ברור שאין לעקם את ההיגיון בפרשנות המציאות.

העולה מדברי כל הראשונים הללו, שגם בעת שדנים לכף זכות אין לעקם את השיקול ההגיוני. כאשר אנחנו רואים צדיק גמור רודף אחר נערה המאורסה, הפירוש שאשתו שלחה אותו להשיב לה משהו שהיא שכחה אצלה הוא הפירוש הסביר. לעומת זאת, אם נראה רשע שעושה זאת, הפירוש הסביר הוא שהוא רוצה לפגוע בה. לכן ההתחשבות במעלתו של האדם בו מדובר היא שיקול הגיוני בתכלית, והחובה לדון לכף זכות באה בעיקר לאסור עלינו לאמץ פירושים לא הכרחיים בכיוון השלילי. בכל אופן, היא ודאי לא באה להורות לנו לאמץ פירושים לא הגיוניים.

נזכיר עוד כי גם לגבי לשון הרע, החפץ חיים כותב שאמנם אין לקבל בהחלטה את הדברים, אבל “למיחש בעי”. כלומר בכל מקרה לא מדובר כאן על החלטות שאינן הגיוניות אלא על אי קבלת החלטות לא הכרחיות לרע.

ובשורה התחתונה עלינו לשאול את עצמנו: אם אכן בהקשרים של דיון לכף זכות יש הסבר סביר שאותו אנחנו דוחים, ומעדיפים על פניו הסבר דחוק אך “מוסרי” יותר, אם כן הדבר אינו עומד בקריטריונים שמעמיד בנימין עצמו. הוא כותב שרק במקום בו האמת העובדתית אינה נגישה לנו יש להעדיף אמת “קיומית”. אבל כאן האמת העובדתית כן נגישה לנו, אז מדוע בכל זאת עלינו להעדיף אמת “קיומית”?

ובכלל, המונח “אמת קיומית” נשמע לי מטריד כבר ברמה הסמנטית. הרב דסלר בספרו מכתב מאליהו כותב שכאשר אנחנו משקרים מסיבה מוצדקת זה אינו “שקר” אלא “אמת”. השקר הוא מה שלא ראוי לומר, ולא מה שלא מתאים לאמת העובדתית. טענות כאלה מעוררות אי נחת. אני מעדיף את הניסוח שזהו שקר מותר ולא שזוהי אמת, כי לא מדובר באמת. אם גם האמת נעשית פלסתר, וניתנת להגדרה שרירותית, מה נותר לנו בעולמנו?! בה במידה, גם המונח “אמת קיומית” נראה לי בעייתי מאד, והוא מזכיר לי במשהו את דבריו המפורסמים של ג’ורג’ אורוול, בספרו 1984, בו הוא עוסק בשטיפת המוח הקומוניסטית: “מלחמה היא שלום, עבדות היא חרות, בערות היא כח”. זה שהשקר הוא מוצדק אינו הופך אותו לאמת. לשון אחר: אין זו “הותרה”, אלא “דחויה”. המונח אמת לעולם משמש במובן של התאמה למציאות. אם מחשבה כלשהי היא נכונה מוסרית זה לא הופך אותה לאמיתית. המונח “אמת קיומית” מטשטש משמעות שמסוכן מאוד לטשטש אותה, בפרט בעולם פוסטמודרני שבו האמת מצויה תחת מתקפה כבדה (ושגויה).

כעת נברר את המעשה ממסכת שבת, ממנו נראה שגישתו של בנימין נכונה. לכאורה מוצעים שם הסברים דחוקים מאוד, והפועל (ר’ עקיבא) מעדיף אותם על ההסבר המתבקש. כיצד עלינו להבין זאת לאור דברי הראשונים שהובאו כאן? ניתן להציע לכך שני הסברים אפשריים:

- המעשה שמתואר בגמרא הוא מעשה קיצוני, ואין ללמוד ממנו למעשה. אולי יש מקום לשבח את הנוהג כך (אם הוא מבין שדבריו אינם תואמים לאמת, אבל הם יאים מבחינה מוסרית), אבל לא נדרש מאיתנו לעשות כן. לדוגמה, חז”ל מספרים שאברהם אבינו האכיל את המלאכים שבאו אליו שלוש לשונות בחרדל, ושחט לשם כך שלושה עגלים. לא סביר שנדרש מכל אחד מאיתנו להשחית שלושה עגלים כדי להאכיל את אורחיו לשונות. הם יכולים להסתפק בחלקים מהפולקע של עגל אחד. הסיפור של אברהם אבינו בא להציג הכנסת אורחים באופן קיצוני ומוגזם כדי להניע אותנו לפעולה, אבל הוא מודל ליישום פרקטי. ייתכן שגם גישתו של ר”ע במקרה זה אינה מציעה מודל לחיקוי פרקטי אלא מודל תיאורטי בלבד.

- סביר יותר שאותו פועל הכיר את המעסיק שלו, ולכן היה ברור לו שהוא צדיק ולא מלין את שכרו ללא סיבה מוצדקת. ולגבי צדיק, הרי כתבו הראשונים הנ”ל שאין להרשיע אותו אף במקום בו הפירוש שמצדיק אותו הוא דחוק ביותר. כפי שהסברנו, הסיבה לכך אינה החובה לפרגן לצדיקים, אלא העובדה שביחס לצדיקים הסברים כאלו כלל אינם דחוקים. ביחס לצדיק, ההשערה שמעשה כלשהו שלו נעשה מתוך רשע אינה סבירה מבחינה הגיונית ועובדתית, ולכן אנחנו לא מניחים זאת לגביו. במילים אחרות, זו לא אמת “קיומית” אלא עובדתית. בעצם נכון יותר לומר פשוט שזוהי האמת (שהרי אין “אמת קיומית”).

ב. תערו של אוקהאם

אקדים ואומר שאת עקרון התער של אוקהאם ניתן למצוא בכמה וכמה הקשרים הלכתיים. אחד הידועים שבהם הוא פירושו של הגר”ח מבריסק לגמרא בריש חגיגה שמביאה שלושה סימני שוטה. הגמרא שם מסבירה שכל אחד מהסימנים אינו אינדיקציה לכך שהאדם שוטה כי יש לו הסבר אלטרנטיבי, וכך גם אם מופיעים שניים מהם. אבל אדם שנוהג בשלושה הקשרים שונים כשוטה – הוא שוטה. שם איננו מחפשים הסבר אלטרנטיבי. זהו שימוש בתער של אוקהאם, שכן אנחנו מאמצים את ההסבר הפשוט ביותר, אף שהוא אינו יחיד ואף אינו הכרחי (ייתכן שיש שלושה הסברים שונים, הסבר שונה לכל סימפטום).

כעת אשאל את בנימין ואת הקורא: אם אתם רואים אדם שבשלושה הקשרים שונים נוהג כשוטה. על מה הייתם מהמרים במישור האונטולוגי: האם אותו אדם הוא שוטה או שמדובר בהצטברות מקרית? אין ספק שכולנו מבינים שהרבה יותר סביר (גם אם לא הכרחי, כמובן) שאותו אדם הוא אכן שוטה. מדוע לא נניח שיש שלושה הסברים שונים? הרי ההסבר שהוא שוטה ודאי אינו הכרחי? התשובה היא שאנחנו מניחים שתערו של אוקהאם הוא דרך להגיע לאמת ולא רק כלי עבודה פרקטי (או קיומי). הטעות ביחס לפרשנות התער של אוקהאם ככלי סובייקטיבי שאינו מיועד להגיע לחקר האמת, נובעת מן הגישה האנליטית שרואה בכל טענה לא מוכחת ולא וודאית טענה שרירותית. אך זוהי טעות. יש טענות שהן אמנם לא וודאיות אך הן סבירות, ואין סיבה שלא לאמץ אותן. התער של אוקהאם הוא כלי שמקרב אותנו לאמת, גם אם הוא אינו ודאי. לכן המסקנה שאותו אדם הוא שוטה סבירה יותר במישור האונטולוגי מהמסקנה שהוא אינו שוטה. זו לא אמת קיומית, והתער של אוקהאם הוא כלי לבירור האמת.

אציין כי הרב קנייבסקי בפירושו למסכת טהרות (קהילות יעקב למסכת טהרות סי’ מז), מרחיב זאת וטוען שכל חזקות ג’ פעמים (חזקת ג’ שנים בקרקעות, וסתות, שור מועד וכדו’) מבוססות על אותה צורת חשיבה. היסוד הוא שלא סביר לאמץ שלושה הסברים שונים לשלוש תופעות, אם יש לנו הסבר אלטרנטיבי יחיד שמסביר את שלושתן כאחת.

לא מדובר כאן בעיקרון קיומי או סובייקטיבי, אלא בעיקרון שנחשב בעינינו ככלי להגיע לאמת (במובן האונטולוגי שלה). מדוע להכריז על שור כמועד אם איננו חושבים שהוא כזה? אם אכן לא ברור אונטולוגית שהוא מועד, אזי חובת הראיה היא על המוציא (=הניזק). הוא הדין לגבי וסתות, גם שם מטרתנו להגיע למצב בו יש חשש אמיתי לראיית דם. לא מדובר על משחקים סובייקטיביים מסיבות שונות, אלא במכשיר שמטרתו לאתר נקודות חשש אמיתיות.

אנחנו רואים שבכל פעם שאנחנו מכניסים יד לאש, היד נשרפת. האם נסיק מכאן שאש תמיד שורפת ידיים שנמצאות בתוכה היא אמת קיומית? האם זו לא אמת עובדתית? זוהי טענה אבסורדית. ההנחה המדעית המקובלת היא שמה שחוזר על עצמו הוא כנראה נכון. זהו עקרון האינדוקציה, ואנחנו מסתמכים עליו כמכשיר להגעה לאמת העובדתית. ערעורו הידוע של דייויד יום על עקרון האינדוקציה מופרך אמפירית (ראה בנספח למאמר). דומני שערעורו של מתן בנימין על כך מבוסס על ערבוב בין הטענה שהאמת הזו אינה ודאית/הכרחית (=בעיית האינדוקציה) לבין הטענה שהיא סובייקטיבית וקיומית. הטענה הראשונה היא כמובן נכונה, אך השנייה בהחלט לא.

דוגמה נוספת לשימוש בתער של אוקהאם בהלכה היא היסק הצד השווה. במכניזם של הצד השווה (=מידת בניין אב משני כתובים) אנו לומדים מדין שקיים בשני מלמדים שונים, על קיומו של הדין במקום שלישי (=הלמד). כל לימוד כזה, ללא יוצא מן הכלל, מופיע במצב בו לכל אחד מהמלמדים יש תכונה ייחודית שפורכת את הדמיון בינו לבין הלמד. רק הצירוף של שניהם “עושה את העבודה”, כלומר מצליח להוכיח את קיומו של הדין בלמד.

כדי להבין את המבנה הזה, נשתמש בדוגמה הבאה (ב”ק ו ע”א): מטרתנו להוכיח שאבן, סכין ומשא שנפלו ברוח מצויה והזיקו מחייבים את בעליהם בתשלום. הגמרא מנסה ללמוד זאת מבור, ודוחה זאת משום שייתכן שבור מחייב מפני שאין כוח אחר מעורב בו. לאחר מכן היא מנסה ללמוד מאש, ודוחה זאת בטענה שלאש יש תכונה מיוחדת שדרכה לילך ולהזיק. כעת היא חוזרת ולומדת משניהם יחד (בצד השווה של שניהם, שהם ממונו ושמירתן עליו, צד שקיים גם באבנו סכינו ומשאו).

בלי להיכנס לפרטי המכניזם הזה,[1] ניתן לראות שיש עוד אפשרות להסביר את המלמדים כך שהמסקנה לא תוכל להיגזר מהם: אש מחייבת בגלל שכוח אחר מעורב בה, ובור מחייב כי תחילת עשייתו לנזק, ואבנו סכינו ומשאו שאין בהם את שני הדברים כלל לא מחייבים בתשלום. בכל ההופעות של הצד השווה בש”ס עולה שאלה דומה (זה מה שקרוי פירכת צד חמור. ראה כתובות לב ע”א, ומכות ד ע”א ומקבילות), ואנחנו לעולם לא עושים פירכה כזו.[2]

הסיבה לכך שאנחנו בוחרים את ההסבר של הצד השווה ולא את ההסבר האלטרנטיבי (של הסבר שונה לכל אחד מהמלמדים) היא התער של אוקהאם. ההסבר שבשני המקרים יש אותו גורם לדין עדיף בעינינו על ההסבר שתולה את הדין בשני גורמים שונים. כעת נחשוב: האם סביר שמדובר ב”אמת קיומית”? האם נכון לחדש דין או עונש על סמך אמת קיומית שאינה עובדתית? מדוע שהמזיק לא יאמר שחובת הראיה היא על התובע ממנו? על כורחנו שגם שם מדובר בכלי שמגיע לאמת (אמנם לא בוודאות, אך בסבירות גבוהה).

הטעות הזו בפרשנות לעקרון התער היא רווחת מאד, ולכן החלטתי להציע כאן את ההוכחה לגישתי (על בסיס מאמרי שלא פורסם, שמצוטט אצל בנימין). הטיעון מציג הוכחה סטטיסטית נגד הגישה ה”קיומית” ביחס לתער של אוקהאם במדע (ובכלל). אני מראה שם שעקרון התער הוא מכשיר להגיע לאמת העובדתית ולא רק דרך סובייקטיבית לסידור המידע שבידינו. הדבר אינו זוקק תפיסות מיסטיות או שיקולים שקשורים לתורת הקוונטים, שמוכיחים שהתודעה האנושית משפיעה על המציאות (ראה אצל בנימין בהערה 4). כדי לא לקטוע את הדיון, ההוכחה מופיעה כנספח למאמר זה.

חשוב לציין שציטוטים כמו זה של איינשטיין, שמעיר כי התיאוריה שלו היא הפשוטה ביותר האפשרית, אך הוא אינו שולל את האפשרות שהתיאוריה הנכונה היא מסובכת יותר, אינם נוגעים לדיון הזה כלל ועיקר. אף אחד לא טוען שהפשוט הוא בהכרח הנכון. הטענה היא שהפשוט הוא כנראה הנכון, אף שייתכן שבמקרים מסויימים זה לא יהיה כך. המדע אינו מתיימר להיות ודאי כמו המתמטיקה או הלוגיקה, ולעולם הספק כרוך בעקבו .

בנימין כותב מיד אחרי הציטוט: “מובן כי העדפת התיאוריה של איינשטיין לא מעידה ולו במעט על המציאות”. האמנם? וכי אישורים כה רבים של הניבויים אפריורי של התיאוריה הזו אינם מעידים על כך שהיא נכונה יותר ממתחרותיה? שוב יש כאן זיהוי לא מוצדק של היעדר ודאות עם ספק ושרירותיות. אכן ההסבר הפשוט אינו בהכרח ההסבר הנכון, אבל בהחלט סביר להניח שהוא ההסבר הנכון. זו הייתה גם כוונתו של איינשטיין כמובן. איינשטיין מתכוון לומר שתיתכן תיאוריה אחרת שתסביר את המציאות, אבל לדעתו היא תהיה מסובכת יותר. הוא לא הציג תיאוריה כזו, ולא ידועה לי תיאוריה מתחרה כזו שמסבירה את כל העובדות. אבל גם אם תהיה תיאוריה כזו, והיא תסביר את כל העובדות באופן מסובך יותר, ההנחה לפי התער של אוקהאם היא שהתיאוריה הפשוטה יותר (זו של איינשטיין) היא כנראה הנכונה. אמנם תיאורטית ייתכן שזה לא המצב, אבל סביר בהחלט שכן.

הראיה העיקרית לכך היא שהתיאוריה של איינשטיין ניבאה תוצאות שנצפו אחר כך בדיוק מדהים. האם זו לא ראיה לאמיתותה? כמובן תמיד ניתן להציע אד הוק תיאוריה אחרת שתתאים לתוצאות הללו לאחר שהן כבר נצפו. אבל עמידה של תיאוריה בניסויים שהיא ניבאה אפריורי את תוצאותיהם היא מדד ברור לנכונותה. גם הבחנה זו נדונה עוד בנספח.

ג. ההשוואה בין הדרישה לדון לכף זכות לבין עקרון התער: ‘קדושתו’ של המדע

ההסתמכות של בנימין על סטיבן הוקינג נראית לי בעייתית. זהו כשל אד הומינם (הסתמכות על סמכות, ובפרט על סמכות לא רלוונטית). בהערה 9 במאמרו בנימין מביא שבמאמר שלי, שטרם פורסם אז, אני מוכיח את הטענה שתערו של אוקהאם הוא כלי לאמת עובדתית, ובכל זאת הוא בוחר משום מה להסתמך על דבריו הלא מבוססים של הוקינג (הוקינג לא מנמק את טענתו). הוקינג הוא אמנם איש מדע חשוב, אך למיטב שיפוטי הוא פילוסוף חלש למדי. כך או כך, לא הייתי ממליץ לאף אחד להסתמך על טיעונים לא מנומקים של מישהו רק על בסיס העובדה שהוא זה שטוען אותם.[3]

באופן כללי יותר, גם אם נניח ששתי הטענות הקודמות היו נכונות (שהחובה לדון לכף זכות דורשת מאיתנו לפעול על סמך שיקולים שאינם קשורים בשום צורה לאמת העובדתית, ושהתער של אוקהאם גם הוא מכשיר “קיומי” כזה), איני רואה כיצד קיומה של בעייה אחת מהווה הסבר או הצדקה לנהוג באופן בעייתי בהקשר נוסף. העובדה שבתחום המדע אנחנו עושים משהו לא מבוסס ולא מוצדק אינה יכולה להוות הצדקה לעשות זאת בתחומים אחרים. אם אכן הייתי מקבל את הפרשנות המוטעית הזו לתער של אוקהאם, לכל היותר הייתי זורק את כל החוקים המדעיים לפח האשפה של ההיסטוריה (מה שאינני עושה, כמובן, כי לדעתי המדע כן מגלה את האמת על העולם, או לפחות מתקרב אליה). איני רואה כיצד העובדה שקבוצה אחת של אנשים (אנשי מדע) עושה דברים ללא הנמקה והצדקה מהווה צידוק לקבוצה אחרת (לומדי תורה, או עובדי ה’) לעשות דברים כאלה. הדבר דומה למילון אנגלי-אנגלי, בו מוסברת לנו מילה לא מובנת אחת באמצעות אוסף של עשר מילים מובנות עוד פחות.

תופעה נפוצה בעולם שמנסה לחבר תורה ומדע היא להתבסס על תופעה תמוהה שקיימת בעולם המדעי (תורת הקוונטים זוכה להתעללויות לא מעטות בנסיבות כאלה), ולהצדיק באמצעותה תופעה הלכתית שאינה תמוהה יותר.[4] נראה כאילו המדע ואנשי המדע זוכים להילת קדושה, ולכן כל תופעה או אמירה תמוהה בהקשרים מדעיים אינן זקוקות להצדקה. להיפך, הם מאצילים מקדושתם על התורה, וכך נפתרות קושיות ובעיות שקיימות בה. איני רואה בדמיוני מישהו שכתב מאמר שמצדיק את עקרון התער של אוקהאם באמצעות המשנה שדורשת לדון לכף זכות וכדו’. כמו כן, לא ראיתי מישהו שמצדיק אמירות בעייתיות של הוקינג ודומיו על סמך משנה או ברייתא תמוהה.

על כך היו שואלים הילדים שלי: ואם אנשי מדע כלשהם היו אומרים לך לקפוץ מהגג, היית קופץ? כשלעצמי, מאז ומעולם העדפתי מילון אנגלי-עברי.

נספח: הוכחה סטטיסטית נגד האמפיריציזם ובעד הרציונליזם[5]

בביקורתי על סעיף ב, יצאתי כנגד גישה נפוצה שמתייחסת לעקרון התער של אוקהאם כעיקרון אסתטי גרידא. בגלל הנפוצות של הגישה המוטעית הזאת, מצאתי לנכון להקדיש נספח להוכחה אמפירית-סטטיסטית לטובת הגישה המנוגדת. הטיעון הוא פשוט למדי, אך אינני מכיר הצגה חדה ובהירה שלו, ולכן אני מציע אותו כאן.

הקונפליקט האקטואליסטי-אינפורמטיביסטי

בפילוסופיית המדע של הדורות האחרונים מתעמתות שתי גישות עקרוניות זו מול זו. אנו נכנה אותן כאן, בעקבות זאב בכלר, “אקטואליזם” ו”אינפורמטיביזם”.[6]

האקטואליזם היא גישה שרואה אך ורק בעובדות האקטואליות מידע מדעי. חוקי המדע, היֵשים התיאורטיים והתיאוריות המדעיות, שהם כולם בעלי אופי לא אקטואלי (הם לא נוכחים מול עינינו), אינם נתפסים בגישה זו כטענות שעוסקות במציאות, אלא כטענות על המדען או על הקהילייה המדעית. התיאוריה, לפי האקטואליזם, אינה אלא סידור נוח ושימושי של מכלול העובדות המדעיות בתחום הנדון. לפי גישה זו, הערך המוסף שיש בתיאוריה לבד מהיותה אוסף העובדות הפרטיות שנצפו בתצפית אמפירית, אינו מכיל כל אינפורמציה על העולם. ומכאן שהיֵשים התיאורטיים שבהם התיאוריה משתמשת אינם אלא פיקציות נוחות המשמשות אותנו באותה שפה שהמדע מפתח כדי לסדר בצורה יעילה ונוחה את מכלול העובדות הידועות לו. במינוח אחר אפשר לראות בגישה כזו אמפיריציזם קיצוני, כלומר עמדה שרואה בתצפית את המכשיר הבלעדי לצבירת מידע על העולם. לפי עמדה זו, ההכללות שעושה החשיבה שלנו על סמך התצפיות, מוסיפות מידע מעבר למה שצפינו בו ישירות, ולכן הן אינן יכולות להכיל מידע על העולם, אלא לכל היותר לספק לנו עיבוד וצורת הצגה מסוימים של המידע האמפירי.

זוהי בדיוק גישתו של בנימין לעקרון התער של אוקהאם. התער מסייע לנו לבנות תיאוריה שתכיל את העובדות הרלוונטיות, אך הוא רואה את התיאוריה כסידור סובייקטיבי של העובדות ולא כטענה שהיא נכונה עובדתית (אלא רק “קיומית”).

האינפורמטיביזם, לעומת זאת, היא גישה, שיהיו שיכנו אותה “נאיבית”, אשר רואה במפעל המדעי תהליך של התקדמות וצבירת ידע על אודות העולם. לפי גישה זו, התיאוריה המדעית טוענת טענות על העולם עצמו. ולענייננו, גישה זו רואה את עקרון התער ככלי להתקדמות לקראת האמת העובדתית. בעלי גישה זו גורסים שהיֵשים התיאורטיים יכולים להיות קיימים (אף שלא בהכרח. ייתכנו תיאוריות שגויות, או תיאוריות פנומנולוגיות – כאלו שאינן מתיימרות לטעון טענות על אודות העולם אלא רק להציע תיאור נוח של קבוצת עובדות שמכוננת תחום מדעי). האינפורמטיביזם רואה בתיאוריה המדעית טענה המכילה תוכן אמפירי מעבר למכלול העובדות האמפיריות הידועות המהוות את הבסיס שממנו נוצרה התיאוריה. במינוח אחר אפשר לראות בגישה זו רציונליסטיוּת, שכן היא מבטאת עמדה שלפיה תוצרים של החשיבה שלנו כשלעצמה (ולא רק של התצפית האמפירית), יכולים להכיל מידע כלשהו על העולם.

ניקח לדוגמה את תיאוריית הכבידה של ניוטון. העובדות הן שגופים שונים נופלים לכדור הארץ. ניוטון הציע הכללה שלפיה כל שני גופים בעלי מסה נמשכים זה לזה, וכמקרה פרטי, עצמים בעלי מסה נמשכים לכדור הארץ. עד כאן זוהי תיאוריה פנומנולוגית, שכן היא רק מתארת מה קורה באמצעות חוק כללי. ההסבר התיאורטי שהציע ניוטון לתופעה הזאת הוא שהמסות מפעילות זו על זו כוח, שמכונה כוח הכבידה, וכוח זה גורם למשיכה ההדדית של הגופים בעלי המסה זה כלפי זה. התיאוריה הזו היא תוצאה של הפעלת התער של אוקהאם, שכן זוהי ההכללה הפשוטה ביותר לאוסף העובדות הרלוונטיות. והנה, האקטואליזם רואה רק את העובדות הפיזיות כקביעות עובדתיות על העולם. עצמים אכן נופלים לכדור הארץ. אולם לשיטתו ההכללה שלפיה קיימת משיכה בין כל שני עצמים בעלי מסה היא השערה בלבד, שכן לא בדקנו את כל הגופים בעלי המסה ביקום. יתר על כן, כוח הכבידה, שהוא היש התיאורטי שמחולל את התופעות האמפיריות הללו, אינו אלא פיקציה שמטרתה הצגה נוחה, מובֶנת ושימושית של העובדות. אנחנו תופסים את העולם כאילו היה בו באמת כוח כזה בין כל שתי מסות. אבל מכיוון שאף אחד לא צפה בכוח הזה עצמו (הוא אינו יש אקטואלי), אין לנו אפשרות לטעון שאכן הוא ישנו במציאות. האינפורמטיביזם, לעומת זאת, רואה את כוח הכבידה כיש קיים, שפועל בעולם, והוא אשר מחולל את התופעות שבהן אנחנו צופים. לשיטתו התער של אוקהאם שהניב את התיאוריה קירב אותנו לאמת העובדתית.

אותה מחלוקת מקרינה גם על תפיסת תפקידו ומעמדו של הניסוי ושל תוצאותיו. לפי הגישה האקטואליסטית, הניסוי המדעי אינו אמצעי להתקדמות לכיוון בניית תיאוריה שתואמת באופן שלם יותר את המציאות, אלא אמצעי לאיסוף של עוד עובדה מדעית השייכת לאותו תחום מדעי, והכנסתה למבנה התיאורטי הפיקטיבי. בונה התיאוריה יצטרך להתחשב גם בעובדה הנוספת הזאת, ולכלול גם אותה במבנה התיאורטי (הפיקטיבי) שאותו הוא יוצר. הצלחה של הניסוי אינה אלא אישוש לכך שהשפה הפיקטיבית שבה משתמשת הקהילייה המדעית אינה דורשת שינוי לעת עתה. היא עדיין מתארת נכון את כל העובדות הידועות לנו. לפי האקטואליסטים כישלון של ניסוי אינו הפרכה של טענה כלשהי על אודות העולם, אלא הוספת עוד בדל מידע שמאלץ אותנו לשנות שפה (ולפעמים גם את היֵשים התיאורטיים אשר נכללים בה), או לבנות תיאוריה שונה שתוכל להכיל ולייצג גם את המידע החדש. כעת, במקום כוח כבידה יהיה עלינו להגדיר מושג תיאורטי אחר שיארגן בעבורנו את כל העובדות.

לעומת זאת, לפי הגישה האינפורמטיביסטית, התיאוריה טוענת טענות על העולם, ולכן הניסוי המדעי הוא אבן בוחן לתקפותה של התיאוריה. אם הניסוי מצליח יש בו משום אישוש לטענה שהתיאוריה אכן מתארת נכון את העולם (שאכן קיים כוח כבידה). אם הניסוי נכשל, התיאוריה הופרכה. במצב כזה המסקנה היא שאין במציאות כוח כבידה, ולכן התיאוריה אינה יכולה לשמש כתיאור הולם של העולם. כעת עלינו לחפש תיאוריה אחרת, שתתאים למכלול העובדות כולו (כולל זו האחרונה).

תחת כל אחת משתי כנפיו של התיאור הסכמטי הזה ישנם כמה וכמה גוונים ובני גוונים של גישות שונות בפילוסופיה של המדע, אולם לצרכינו די לנו בסכמה הכללית הזאת.

האם המחלוקת הפילוסופית הזאת עוסקת בשאלה אמפירית?

שתי הגישות הללו תופסות באופן שונה את העולם, ובעיקר את המדע. האקטואליזם רואה את העולם כמכלול של עובדות פרטיקולריות. החוקים הם קונסטרוקציות סובייקטיביות, או בין-סובייקטיביות, שמתבצעות בתוך הקהילייה המדעית, אך בהחלט אינן תיאורים של העולם עצמו. גם אם נניח כי תיאורטית ישנם חוקים כוללים כאלה במציאות עצמה (לא ברור על סמך מה אנו מניחים זאת) אין באפשרותנו לגלות אותם באמצעים אמפיריים. האמפיריקה מאפשרת לנו להבחין אך ורק בעובדות פרטיות ולא בחוקים כלליים. לעומת זאת, האינפורמטיביזם רואה בעובדות הפרטיקולריות ביטויים שונים של חוקי טבע כוללים. המדע אמור להתקרב ככל האפשר לתיאור מלא של החוקים האמיתיים, אלו שקיימים באמת, ולכן הם גם מהווים תיאור מהימן של העולם עצמו. המסקנה מן האמור עד כאן היא שהמחלוקת הזאת אינה רק מחלוקת באשר לאינטרפרטציה פילוסופית גרידא, אלא היא עוסקת במציאות העובדתית. די ברור שזוהי מחלוקת עובדתית, שעניינה, לדוגמה, שאלת קיומם של היֵשים התיאורטיים שנוצרים בתיאוריה המדעית. השאלה אם יש כוח כבידה או לא, היא שאלה עובדתית, ולכן מחלוקת לגביה היא מחלוקת בנושא עובדתי.

כעת עלינו לשאול את עצמנו, האם יש דרך אמפירית להכריע בשאלה עובדתית זו? מקובל לחשוב שלא. לכאורה נראה כי שתי הגישות הללו גם יחד נמצאות בעולם התיאורטי-פילוסופי, ולא בספירה האמפירית. הן עוסקות רק במטא-מדע, ובמשמעות התהליך המדעי, ולא בתכניו. כלומר אמנם זו מחלוקת באשר לעובדות, אבל היא אינה מחלוקת מדעית, שכן אין לנו בהכרח דרך אמפירית להכריע בה.

זהו תיאור מן הזווית של תכני העמדות הללו. אולם אפשר לבחון אותן גם מן ההיבט המתודולוגי, וגם בבחינה זו נראה כי אין הבדל של ממש בין שתי הגישות, שכן שתיהן מתארות בדיוק באותה צורה את התהליך המדעי. הוא אמור להתנהל בדיוק באותו אופן על פי הדוגלים בכל אחת משתי ההשקפות הללו. הן לפי הגישה האקטואליסטית והן לפי הגישה האינפורמטיביסטית, המדע אמור להכליל את העובדות הידועות לו, ולעשות זאת באמצעות יֵשים תיאורטיים וקונסטרוקציה תיאורטית שמלכדת אותם לכלל מבנה קוהרנטי, ולבסוף לבחון את עצמו באמצעות ביצוע ניסויים שבודקים ניבויים (פרדיקציות) של התיאוריה שהוא יצר. הצלחה של הניסוי תותיר את המבנה על כנו, ואילו כישלון שלו יאלץ אותנו להחליף את התיאוריה.[7] לכאורה ההבדל בין שתי הגישות הללו עוסק רק במשמעותו של התהליך הזה, ולא בצורתו ובמאפייניו. לא ייפלא אפוא ששתי הגישות הללו ממשיכות להתעמת במשך ההיסטוריה (ראו אצל בכלר) ללא הכרעה ברורה. התנודות הזמניות של המטוטלת במחלוקת הזאת הן תוצאה של אופנות יותר מאשר של טיעונים, ובוודאי לא של ניסויים. המסקנה המקובלת היא כי ההכרעה בין שתי העמדות הללו אינה נתונה לשום מבחן אמפירי. ואכן לא ייפלא שגם בכלר, לאורך כל הספר שלו, אינו מציע שום מבחן שיכריע לטובת עמדתו האינפורמטיביסטית הנחרצת, ונגד האקטואליזם שנוא נפשו. הוא עוסק יותר בתיאור שתי העמדות ובהטפה לטובת האינפורמטיביזם והשמצת האקטואליזם, ומעט מאוד בהנמקה עקרונית. יתר על כן, בהיעדר אפשרות להכריע במחלוקת הזאת נראה שעלינו לבחור דווקא באקטואליזם, שכן עקרון התער של אוקהאם מורה לנו לבחור את האפשרות שבה מספר היֵשים קטן ככל האפשר. טיעון זה מחדד את הצורך בהנמקה ממשית לטובת האינפורמטיביזם, אם אכן ברצוננו לאחוז בו.

הסיבות למחלוקת

ראינו שהמחלוקת האקטואליסטית-אינפורמטיביסטית עוסקת במציאות. וכמו כן, ראינו שאין כל דרך אמפירית להכריע בה. אז מדוע באמת נוצרה מחלוקת כזו? אם העובדות אינן מאפשרות לנו לגבש עמדה כלשהי, מה בכל זאת גורם להוגים שונים לאחוז בכל אחת משתי העמדות הללו? הדברים מתבהרים על רקע הקביעה האחרונה, שלפיה תערו של אוקהאם הוא שמטה את הכף לטובת האקטואליזם. מסתבר אפוא ששורשיה של המחלוקת נעוצים בחשיבה אפריורית ולא בעולם העובדתי.

כדי להבין זאת, אסתכן תחילה בניחוש: רוב גדול של המדענים (הדבר ודאי נכון באשר לאלו המוכרים לי אישית) דוגלים בגישה האינפורמטיביסטית, שהיא האינטואיטיבית יותר. אין סיבה להניח שיש חוק כבידה אם אין במציאות כוח כבידה שמחולל אותו (לפי האקטואליזם, זהו יש תיאורטי פיקטיבי, שנוצר על ידינו רק לצורך השלמות והנוחות התיאורטית). לעומת זאת, רוב הפילוסופים של המדע נוטים, במידה כלשהי, דווקא לכיוון האקטואליסטי (ראו על כך אצל בכלר). מבחינתם אינפורמטיביזם הוא נאיבי, שכן מאמצים שם את ההנחה בדבר קיומם של יֵשים שאין לנו שום דרך לאשש אותה אישוש אמפירי (התער של אוקהאם).

מה גורם להוגים האקטואליסטים לפנות רחוק כל כך מהאינטואיציה? אם אכן אין עובדות אמפיריות שמתנגדות לאינטואיציה האינפורמטיביסטית, אז מדוע לסטות ממנה? מדוע להניח שיש חוק כבידה אבל אין כוח כבידה שמחולל אותו? מסתבר שהסיבה לאימוץ תפיסה אקטואליסטית אכן אינה נעוצה בתחום העובדתי אלא במישור הפילוסופי. ישנה בעייתיות פילוסופית שמלווה את האינפורמטיביזם, ומחמת אופייה הפילוסופי המובהק רבים מאנשי המדע כנראה אינם מודעים לה.

כאמור, האינפורמטיביזם תופס את התיאוריה המדעית כתיאור של העולם עצמו. הוא רואה בתיאוריה המדעית משהו מלבד מכלול העובדות שמהוות את הבסיס שלה. אולם מאז דייוויד יום ברור שההכללות אשר מהוות את לִבה של כל תיאוריה מדעית, והמשגת היֵשים התיאורטיים במסגרתה, יֵשים אשר בהם אי-אפשר לצפות באופן ישיר (לפחות בעת בניית התיאוריה. שאם לא כן, לא היו אלה “יֵשים תיאורטיים”), הם תוצר של חשיבה אינדוקטיבית, לא של תצפית אמפירית. להכללה כזו יש אופי אפריורי, ולכן קשה לבסס את הטענה שהיא אמורה להתאים באופן כלשהו לעובדות בעולם, או אפילו לטעון משהו על אודותיהן. העובדות הפרטניות שמהוות את הבסיס האמפירי לתיאוריה הן עובדות שבהן אנחנו צופים ישירות (באמצעות החושים או באמצעות מכשירי מדידה). אולם ההכללה התיאורטית שמבוצעת על בסיסן היא מבנה אפריורי, אשר תלוי בעולמם של המדען או הקהילייה המדעית (מה שתומס קון מכנה “פרדיגמה”), בצורת החשיבה ובעולם המושגים שלהם, וככזה הוא אינו יכול לטעון טענות על אודות העולם. אדם אחר, או קהילה אחרת, היו מגיעים למבנה תיאורטי שונה. מסיבה זו, טוען האקטואליסט, התיאוריה אינה יכולה להכיל מידע אמפירי נוסף, לבד מאוסף העובדות שמכוננות אותה. היא פועל יוצא של הקהילייה שמשתמשת בה, ולא של העובדות. דומה כי לבד מהתער של אוקהאם זהו הבסיס העיקרי לאימוץ גישות אקטואליסטיות, וכל כולו נמצא בספירה הפילוסופית, ולא במדעית-עובדתית.

פתרונות שמציעים בסיס פילוסופי לאינפורמטיביזם

קאנט ניסה להתמודד עם הבעייתיות היומיאנית והציע אפשרות לבסס את ההכללה המדעית בדרך מקורית. האפשרות לראות בתיאוריה תיאור של המציאות עצמה על אף מקורה האפריורי-סובייקטיבי, טוען קאנט, נעוצה במגבלות שמכוננות את העולם הפנומנלי (עולם התופעות, או העולם כפי שהוא מופיע לעינינו, להבדיל מהעולם כשהוא לעצמו) שבו עוסק המדע. לפי קאנט המדע איננו עוסק בעולם כשהוא לעצמו, אלא בעולם הפנומנלי. אנו רואים תהליכים באופנים מסוימים, רק משום שאילוצי ההכרה שלנו (שקאנט מכנה אותם עקרונות טרנסצנדנטליים) מכתיבים לצורות הללו להופיע כך לעינינו. ההכללה, הוא טוען, היא אמנם תוצר של החשיבה שלנו, אבל גם העולם שבו אנחנו עוסקים אינו בלתי-תלוי בחשיבתנו. אנחנו לא צופים בעולם כפי שהוא לעצמו, אלא בעולם כפי שהוא מופיע לעינינו, וזהו תוצר של הקטגוריות שבמסגרתן פועלות החשיבה וההכרה שלנו. משפטים שנגזרים מהמתודה הטרנסצנדנטלית קרויים אצלו “משפטים סינתטיים-אפריורי” (משפטים שטוענים טענות על העולם – סינתטיים, ובד בבד הם אפריוריים – כלומר לא נובעים מתצפית).

שיקול דומה יוליך אותנו למסקנה שגם חוקי הטבע, שהם הכללות של העובדות האמפיריות הפרטיקולריות, הם סוג של משפטים סינתטיים-אפריורי. על פי ההצעה הקאנטיאנית, הם אפשריים ותקפים דווקא מפני שהם אינם עוסקים בעולם עצמו (בנואומנה) אלא בתמונה שיש לנו על אודותיו (בפנומנה).

ככל הידוע לי, אין בתולדות הפילוסופיה שום תשובה אחרת לטיעוניו הספקניים של יום, כלומר, אין חלופה להצעה הקאנטיאנית. ולענייננו, אין ביסוס פילוסופי אחר ליכולת שלנו להסיק מסקנות באמצעים אפריוריים-רציונליים על העולם עצמו. ומכאן שגם אין הסבר או בסיס משכנע לתפיסה שרואה ביֵשים התיאורטיים יֵשים ממשיים, ובתיאוריה מכלול של טענות על העולם, כלומר, לאינפורמטיביזם.[8]

הבעייתיות שבביסוס הקאנטיאני – דוגמת החוק השני של ניוטון

אולם כפי שכתבו רבים, הביסוס הקאנטיאני הוא בעייתי.[9] ניטול כדוגמה את החוק השני של ניוטון, שלפיו: a m F =. F הוא הכוח המופעל על הגוף,m היא המסה של הגוף, ו-a היא התאוצה שלו. לצורך הדיון נניח שחוק זה התקבל מהכללה שנעשתה על פי כמה וכמה תצפיות אמפיריות פרטניות. ראינו בכמה ניסיונות שבהם פעל כוח נתון על גוף בעל מסה נתונה, כי התאוצה שהתפתחה מתאימה לחישוב שעולה מהחוק השני של ניוטון. כעת אנו מכלילים זאת וקובעים שזהו היחס בין התאוצה לכוח בכל מקרה שבו יפעל כוח על מסה.

מהו הבסיס להכללה זו? האקטואליסטים יאמרו שבאמת אין לנו כל בסיס סביר בעבורה, אך הכללה זו היא יעילה ונוחה, ובינתיים היא גם מתאימה לכל העובדות הידועות לנו, על כן אנו משתמשים בה כל עוד הדבר אפשרי, כלומר כל עוד לא נצפתה תוצאה של ניסוי שאינה מקיימת את החוק הזה. לעומת זאת, האינפורמטיביסטים רואים בחוק השני של ניוטון טענה על העולם. העולם עצמו מתנהג כך, ומהניסויים הללו גילינו את הקשר המהותי והאמיתי בין כוח למסה ולתאוצה בעולם עצמו.

השאלה המתבקשת היא מהי ההצדקה לראות דווקא בהכללה הזאת את ההכללה האמיתית? הרי היה אפשר להכליל את העובדות באינספור צורות נוספות, שכולן יתאימו למכלול העובדות כולו (ראו בהמשך דברינו פירוט של טענה זו). כאן נשקלת בדיון שאלת פשטותה של התיאוריה. בדרך כלל מקובל שההכללה הפשוטה ביותר היא ההכללה הנכונה.[10] אך ברור שהעובדה שהכללה כלשהי היא הפשוטה ביותר אינה ערובה לתקפותה האמפירית. מדוע להניח שהפשטות היא מדד הולם לאופן התנהלותה של המציאות עצמה? הפשטות היא תוצאה של מבנה החשיבה שלנו, אבל העולם אינו חייב להתחשב בצורת החשיבה שלנו. מסיבה זו גורס האקטואליזם שהפשטות היא אכן קריטריון רלוונטי לאימוץ התיאוריה על ידי הקהילייה המדעית, משום שזו הערובה להיותה של התיאוריה יעילה ושימושית (גם אם לא אמיתית). ואכן, אין שום קשר בין פשטות אינטלקטואלית לאמיתיות עובדתית. מנגד, האינפורמטיביזם רואה בקריטריון הפשטות אינדיקציה לאמיתיות, שהרי בעיניו התיאוריה מתארת את העולם כשהוא לעצמו, ולא רק את אופן החשיבה של קהיליית המדענים בתחום הנדון. מהי ההצדקה לתפיסה “מיסטית” שכזו? כיצד יסביר האינפורמטיביסט את הקשר בין פשטות לאמיתיות? כיצד הוא מגיע להנחה שישנה התאמה בין צורת החשיבה שלנו (שהפשטות נגזרת ממנה) ובין העולם כשלעצמו?

ההנמקה הקאנטיאנית של הסינתטי-אפריורי מסבירה כי להכרה האנושית ישנם אילוצים טרסצנדנטליים (קודמים לניסיון) אשר מעצבים את העולם באופן כזה שהוא יופיע לעינינו בצורות שנגזרות מאילוצי החשיבה וההכרה שלנו. ובדוגמה שלנו, משמעותו של ההסבר הקאנטיאני היא שאילוצים אלו מונעים מאיתנו להבחין בגוף שמאיץ בתאוצה שאינה פרופורציונית לכוח שמופעל עליו. מסיבה זו אנו רואים את הגופים מאיצים לפי החוק השני של ניוטון, וכך גם נמשיך לראות תמיד. לפי קאנט זו אינה טענה על העולם כשלעצמו אלא על העולם כפי שהוא מופיע לעינינו, אלא שזהו העולם שבו עוסק המדע.

אך טענה זו היא בעייתית מאוד. האם תופעה שבה גוף בעל מסה מאיץ לפי ריבוע הכוח, או פונקציה אחרת של הכוח, אינה ניתנת לתצפית חושית? מסתבר שאין כל מניעה שמערכות התפיסה שלנו יבחינו ויקלטו תאוצות שאינן תואמות לחוק השני של ניוטון. נניח שיש לפנינו גוף שמסתו 2 והכוח שמופעל עליו הוא 4, האם כשגוף זה יפתח תאוצה של 3 לא נצליח להבחין בו (התאוצה במקרה זה לפי החוק הניוטוני היא 2)? גם אם ישנם אילוצים טרנסצנדנטליים שבונים אפריורית את החשיבה שלנו, מדוע להניח שאותם אילוצים עצמם גם מאלצים את התפיסה ההכרתית שלנו? האם באמת מישהו חושב שפיזית העיניים שלנו לא יצליחו להבחין בגוף שנע בתאוצה שפרופורציונית דווקא לריבוע הכוח? כיצד קיומו של כוח כלשהו בעולם יכול להשפיע על הראייה שלנו, ולמנוע ממנה לצפות בתופעות שבמצבים אחרים אין לה שום בעיה לצפות בהם? בדרך כלל העיניים שלנו יכולות לצפות בגוף שמאיץ בתאוצה של 3, אך לפי קאנט זה נכון רק כאשר פועל עליו כוח מתאים. במצב אחר אנחנו פשוט לא נצליח להבחין בו. מדוע לא נוכל לראות את הגוף מאיץ בתאוצה 3 גם כשפועל עליו כוח חלש יותר? זה נשמע טיעון אבסורדי, ובוודאי ספקולטיבי מאוד (אף אחד לא הציע מנגנון שיתאר את ההשפעות המיסטיות הללו על ההכרה שלנו).

אם כן, נראה שקשה מאוד להצדיק בצורה כזו את התפיסה שהחוק השני של ניוטון, שלפיו התאוצה פרופורציונית לכוח המופעל על הגוף (ומקדם הפרופורציה הוא המסה), היא אכן תיאור נכון של העולם. יתר על כן, התאמתו של החוק הזה למכלול העובדות הידועות אינה ייחודית. להלן נראה שאפשר להציע אינספור הכללות אחרות שיתאימו גם הן למכלול העובדות שידועות לנו.

כעת אנו יכולים לראות מדוע האקטואליזם הוא אכן התפיסה המתבקשת ברובד הפילוסופי באשר למעמדן ולמשמעותן של תיאוריות מדעיות, אף על פי שהאינפורמטיביזם הוא אינטואיטיבי יותר. כעת מובן מדוע פילוסופים של המדע, אשר מטבע הדברים מודעים יותר לבעייתיות הפילוסופית הזאת, נוטים דווקא לכיוון האקטואליסטי, וזאת שלא כמו אנשי המדע שתופסים את עבודתם תפיסה אינטואיטיבית יותר ופילוסופית פחות.

ההוכחה לאינפורמטיביזם: השלכה סטטיסטית של המחלוקת הפילוסופית

כעת ברצוני לטעון כי שלא כמו האמונה הרווחת, השאלה האקטואליסטית-אינפורמטיביסטית דווקא ניתנת להכרעה אמפירית. אציע כאן שיקול סטטיסטי אשר מוכיח את האינפורמטיביזם. אם הטיעון שאציע הוא תקף, הרי המחלוקת האקטואליסטית-אינפורמטיביסטית מוכרעת לטובת האינפורמטיביזם, וזאת לא משיקולים פילוסופיים בלבד, אלא משיקולים מדעיים לגמרי. מובן שהקושי הפילוסופי שקיים באשר לאינפורמטיביזם, שעליו הצבענו בסעיף הקודם, בעינו עומד. בהמשך דברינו ננסה להצביע על כיוון אפשרי לפתרונו, אך זה אינו עיקר ענייננו כאן. לענייננו, משמעותה של הוכחה לטובת האינפורמטיביזם היא שהתער של אוקהאם הוא מכשיר לתפיסת האמת העובדתית, ולא כלי סובייקטיבי שמשמש אותנו רק לצרכים של נוחיות ויעילות.

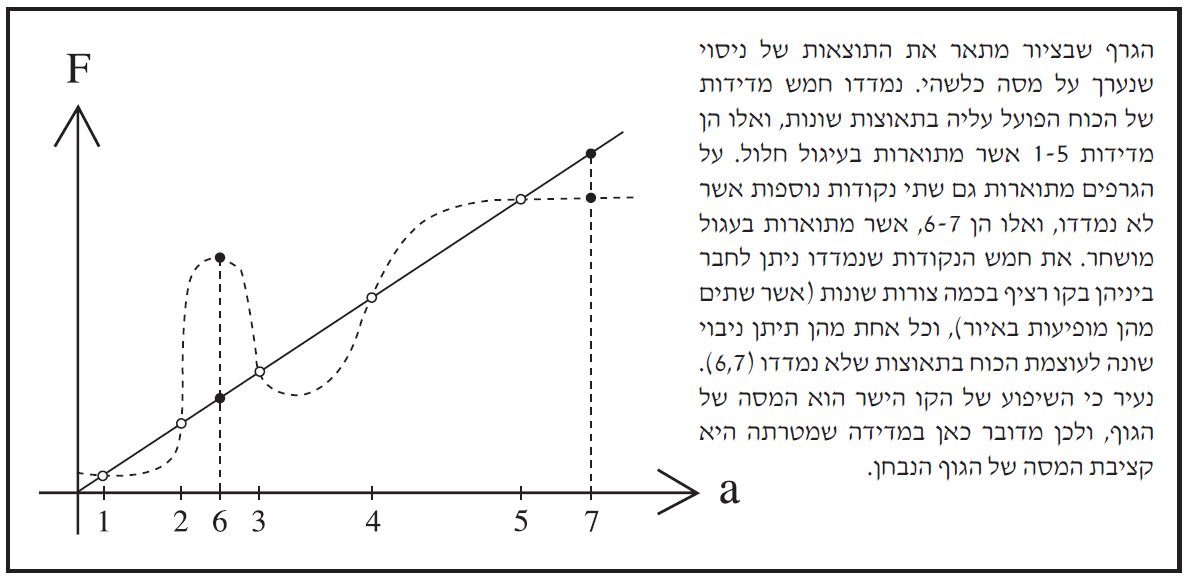

נשוב כעת לחוק השני של ניוטון ונבחן אותו מחדש. נניח שביצענו אוסף של חמישה ניסויים על גוף שמסתו m, ומדדנו את התאוצות שלו בעבור חמישה ערכים של כוח שפעל עליו (5-1). התוצאות של הניסוי מוצגות כעיגולים קטנים וריקים על הגרף המשורטט כאן:

חמש התוצאות נמצאות על קו ישר, ולכן ההכללה המתבקשת לאור עקרון התער של אוקהאם היא להעביר קו ישר שמחבר אותן, ששיפועו הוא המסה של הגוף הנמדד. זוהי ההכללה הפשוטה ביותר. במצב כזה הקהילייה המדעית מחליטה שהיחס בין הכוח ובין התאוצה שאותה מפתח הגוף שעליו פועל הכוח הוא יחס ישר, ומקדם הפרופורציה הוא המסה. חוק הטבע שמצאנו בניסוי הזה אומר שיש יחס ישר בין כוח לתאוצה (זהו החוק השני של ניוטון).

אולם עובדה מתמטית פשוטה היא שישנן אינסוף צורות הכללה אחרות בעבור חמש התוצאות הללו, שכולן תתאמנה לכל החמש. או במילים אחרות, ישנו מספר אינסופי של קווים רציפים שיחרזו את חמש העובדות הפרטניות, כלומר את חמש הנקודות הנתונות בגרף. נעיר כי מספר האפשרויות אינו רק גדול, אלא אינסופי (אינסוף שאינו בן מניה). אחת מהן משורטטת בצורת קו מקווקו על הגרף שלמעלה, ומובן שישנם אינסוף קווים אפשריים כאלה.[11] בנימין במאמרו טוען שאנו דוחים את האפשרות של קו לא ישר מפני שהיא לא פשוטה דיה, ואין לנו עניין באפשרויות מורכבות שאין להם השלכה אמפירית. להלן אראה היכן הוא טועה.

כיצד נכריע בין האפשרויות השונות? מהי בעצם התיאוריה הנכונה, או החוק הכללי הנכון, בעבור תוצאות הניסוי הזה? כאמור, מסתבר שאנו ניטול את האפשרות הפשוטה מביניהן, כלומר את הקו הישר. האקטואליסט יסביר שזוהי האפשרות הנוחה יותר, ואנו מאמצים אותה כל עוד היא לא הופרכה (מקביל לטענתו הנ”ל של בנימין). בעיניו אין כאן טענה על היחס האמיתי בין הכוח לתאוצה, אלא הצגה שהיא היעילה והקומפקטית ביותר בעבור חמש העובדות הפרטיקולריות הידועות לנו, וארגונן בביטוי מתמטי פשוט. לעומתו, האינפורמטיביסט יאמר שהקו הישר הוא האפשרות הנכונה, שכנראה גם מתארת באופן הולם את העולם עצמו. שלא כמו האקטואליסט, האינפורמטיביסט גם נוטה לחשוב שניסוי עתידי יאשר את החוק הזה. מובן שגם האינפורמטיביסט יסכים שניסוי עתידי עלול להפריך את התזה הזאת, ולכן הוא רואה בה עובדה מותנית, שתלויה בתוצאות אמפיריות עתידיות.

כאמור, הן לפי האקטואליסט והן לפי האינפורמטיביסט, השלב הבא של המחקר יהיה עריכת ניסוי נוסף, בעוצמת כוח אחרת, ומדידת התאוצה במצב זה (ראו נקודות 7-6 בגרף). אם הניסוי “יצליח”, כלומר, ערך התאוצה בנקודות אלו יימצא גם הוא על הקו הישר, התיאוריה תיוותר על כנה (נכונה על תנאי – לפי האינפורמטיביסט; יעילה ונוחה – לפי האקטואליסט). אם הניסוי “ייכשל”, כלומר, התוצאה לא תימצא על הקו הישר, התיאוריה תוחלף. החוק החדש יהיה הגרף של הקו הפשוט ביותר אשר חורז את שש העובדות האמפיריות הידועות לנו (חמש הראשונות והנקודה המייצגת את המדידה האחרונה). במצב כזה, לפי האינפורמטיביסט התיאוריה הופרכה, ולפי האקטואליסט יש להחליף שפה. בינתיים עדיין אין שום הבדל מעשי בין שניהם, כפי שראינו גם למעלה.

אולם כעת נשאל את עצמנו את השאלה הזאת: מהו הסיכוי שהתוצאה הבאה (השישית במספר) אכן תיפול גם היא על הגרף הנוכחי (כלומר על הקו הישר)? מתברר שכאן, למרבה הפלא, התשובה תלויה בשאלה אם אנו יוצאים מנקודת מבט אינפורמטיביסטית או מנקודת מבט אקטואליסטית. משניווכח בזה, מצאנו הבחנה אמפירית בין שתי הגישות ה”פילוסופיות” הללו.

נתחיל בתיאור מנקודת מבט אקטואליסטית. כאמור, ישנן אינסוף אפשרויות הכללה של חמש הנקודות הנתונות, והקו הישר הוא רק קו אחד שנבחר שרירותית (משיקולי נוחות גרידא) מבין כולן. ישנן גם אינסוף תוצאות אפשריות לניסוי העתידי (כל הערכים באים בחשבון אפריורי). אם כן, הסיכוי שהתוצאה הבאה תיפול גם היא בדיוק על הקו הישר הוא אפס בדיוק (בפרופורציה הפוכה למספר האפשרויות).

יש לזכור שלפי האקטואליסט חמש הנקודות הידועות אינן מועילות לנו במאומה לידיעת חוק הטבע הכללי, או הקו ה”נכון”. הקו מתאר בנוחות אך ורק את התוצאות שכבר נמדדו, ובאשר לעתיד הוא אינו אומר מאומה. לשיטתו של האקטואליסט כל הקווים באים בחשבון, ובהיעדר מידע אחר הסיכוי לקבל את כולם הוא שווה. הוא בוחר בקו הישר רק מפאת פשטותו, ולא משום שהוא הנכון יותר. אם כן, לשיטתו חמש התוצאות הידועות אינן רומזות לנו דבר על הקו הנכון, ולכן גם אינן רומזות על תוצאת הניסוי הבא. לשיטתו כל הקווים הם שווי הסתברות, ולכן הסיכוי שכל אחד מהם הוא הנכון הוא אחד חלקי מספר הקווים האפשריים, כלומר 0.

לעומת זאת, האינפורמטיביסט רואה בהכללה של הקו הישר הכללה מועדפת (שכן לשיטתו עקרון התער של אוקהאם הוא כלי להכרת המציאות העובדתית). אמנם זו אינה הכללה ודאית, שכן ניסוי עתידי עשוי להפריך אותה, אבל היא בהחלט נחשבת על ידו תוצאה כללית שהתקבלה מחמשת הניסויים הראשונים. הוא רואה בה תיאור (הכי טוב לרגע זה) של המציאות האמיתית, ולא רק כלי יעיל ונוח לסידור חמש העובדות שכבר נמצאות בידיו. בעיניו הקו הישר הוא ההצעה הטובה והנכונה ביותר לתיאור המציאות כפי שהיא נראית לנו עד כה, שהרי לשיטתו הפשטות (=עקרון התער) היא קריטריון לאמיתיות. על כן הסיכוי שהניסוי הבא יאשר את הקו הישר אינו 0, אלא סיכוי גבוה יותר. הוא כמובן לא יתפלא לגלות שהניסוי הבא, השישי במספר, יניב את התוצאה הצפויה על פי חוק הקו הישר. מה הסיכוי לדעתו שכך אכן יקרה? אמנם זה לא ודאי (אם מדובר באינפורמטיביסט שקול והגיוני, שמביא בחשבון את האפשרות לטעות), אבל ברור שהסיכוי אינו אפס. האפשרויות השונות אינן שוות הסתברות בעיניו, ולכן אין לחשב את הסיכוי לפי מספר האפשרויות.

יסוד הדברים הוא שהשיקול הסטטיסטי מנקודת המבט האינפורמטיביסטית הוא שונה מזה שמתקבל בתמונה האקטואליסטית. מבחינת האינפורמטיביזם, אינסוף ההכללות האפשריות אינן שקולות זו לזו, אפילו אפריורי. לכן ההסתברות לכל תוצאה אף היא שונה. האפשרות הפשוטה היא מועדפת, משום שלשיטתו הטענה הפשוטה היא זו הנושאת מידע על אודות העולם. ההכללה הפשוטה נבחרה כי היא נכונה יותר ולא רק משום שהיא נוחה יותר. מכיוון שהיא אינה נבחרת בחירה שרירותית, מבחינת האינפורמטיביסט הסיכוי לכך שהיא נכונה אינו שווה לכל האחרות, כלומר אינו 0.

מובן שגם האינפורמטיביסט יצפה שלא מעט ניסיונות אכן ייכשלו. אך בלי להיכנס להערכה סטטיסטית של כמות הניסיונות שצפויים להיות “מוצלחים” (זוהי, כמובן, שאלה סבוכה ביותר), ברור שהאחוז שלהם מכלל הניסיונות שנערכים אינו אמור להיות אפס. לצורך ההוכחה כאן די לנו בזה.

נעיר כי עדיין לא הצדקנו את העמדה ה”מוזרה” הזאת, שרואה בפשטות קריטריון לאמיתיות, אך לצורך הדיון כעת אנו תופסים אותה כהיפותזה שנבחנת אמפירית מול ההיפותזה האקטואליסטית. שאלת ההצדקה הפילוסופית של ההנחה האינפורמטיביסטית תידון בקצרה להלן.

ההוכחה הסטטיסטית נגד האקטואליזם

עד כאן תואר שיקול סטטיסטי, אך עדיין לא הצבענו על ההיבט האמפירי שלו. איך בוחנים ומכריעים מבחינה אמפירית את הדילמה האקטואליסטית-אינפורמטיביסטית? כפי שראינו, בכל מקרה שניסוי ספציפי כלשהו מצליח או נכשל, אין בכך כל בעיה, לא מבחינת האינפורמטיביסט וגם לא מבחינת האקטואליסט. הרי תוצאה כלשהי צריכה לצאת בניסוי גם לפי האקטואליסט.

כדי להכריע בדילמה הזאת נשאל את עצמנו האם באמת מבחינה סטטיסטית בתולדות המדע עד ימינו מספר הפעמים שבהן ניסויים שנערכו לשם בחינת היפותזות תיאורטיות הצליחו לאשש את התיאוריה הוא אפסי? האם אכן המדע כמעט לעולם אינו מצליח לנבא תוצאות של ניסוי? אם אכן כך היה, הרי גם במאה העשרים ואחת עדיין היינו שרויים באפילה מדעית גמורה. כל הכללה מדעית היתה מופרכת בכל ניסוי שהיה נערך לבחינתה, שהרי הסיכוי להצליח בניסוי כזה הוא אפס (שכן ההכללה היא שרירותית), ולכן היא הייתה אמורה להיות מוחלפת באחרת, וחוזר חלילה עד אין-קץ. כל ניסוי היה מביא להחלפת תיאוריה, ולא הייתה כל התקדמות. לפי האקטואליזם אין כל סיכוי אפריורי לכך שדווקא ההכללה אשר בחרנו בה בחירה שרירותית, אך ורק בזכות פשטותה ונוחות השימוש בה, תעמוד במבחן אמפירי גם בניסוי הבא. התוצאה של ההנחה האקטואליסטית היא שהמדע לא היה יכול להצליח לנסח אפילו חוק טבע אחד שעומד במבחן אמפירי כלשהו (או שפה מדעית אחת, בלשונם, שתוכל להתאים לאוסף כלשהו של עובדות בלי להשתנות מחדש בכל ניסוי וניסוי).

כדי לחדד את הדברים, אוסיף שמתוך נקודת מבט כזו היה אסור לנו להיכנס למכונית או למטוס, שכן הניסויים שערכנו כדי לנסח את חוקי הפיזיקה, שעומדים בבסיס הטכנולוגיות הללו, וכך גם הניסויים של הטכנולוגיה הזאת עצמה, הם חסרי בסיס. אין כל סיכוי שההכללות שאותן הניבו הניסויים הללו יעבדו גם בניסוי הבא, שאותו אנו עומדים לערוך כעת (הטיסה הזאת, שבה אנחנו עתידים להמריא). לפי האקטואליזם, המטוס נבנה על בסיס הכללות שלבד מפשטותן התיאורטית אין להן דבר וחצי דבר עם האמת העובדתית כלומר עם המציאות הריאלית (בדיוק כפי שמציע בנימין במאמרו).

כעת נוכל לראות כיצד אפשר לערוך מבחן אמפירי של שתי התזות הללו. למעשה, הוא כבר נערך מזמן. הדבר פשוט, יש לערוך סקר של הניסויים המדעיים שנערכו במשך ההיסטוריה, או בתקופתנו שלנו, ולראות מהו אחוז הניסויים שמצליחים לתמוך בתיאוריה? באיזה אחוז מהניסויים המדעיים מתאשרים הניבויים של התיאוריה הנבחנת? לחילופין, כדאי לחשוב אם המדע אכן קופא במקום מאז היווסדו, או שמא אנחנו בכל זאת מתקדמים. העובדה שיש אחוז לא אפסי של ניסיונות מדעיים מוצלחים, כלומר, ניסיונות שבהם התיאוריה מנבאת נכון את התוצאה (אלו הניסיונות שמאששים את התיאוריות שלנו) יש בה משום הוכחה אמפירית (סטטיסטית) בזכות עצמה נגד האקטואליזם. מתוך מבט אקטואליסטי לא היה כל סיכוי לראות ניסוי מוצלח, ולו אחד, בשום תחום מדעי.

לסיכום, העובדה שלא כל הניסיונות המדעיים נכשלים, ושיש כמה וכמה תיאוריות מדעיות שעומדות במבחנים אמפיריים ושמצליחות לנבא תוצאות של ניסויים עתידיים, היא כשלעצמה הוכחה אמפירית-סטטיסטית חד-משמעית נגד האקטואליזם. לפי האקטואליזם תופעה כזו היא בלתי-אפשרית (כלומר בעלת סבירות נמוכה ביותר).

הערה על הגישה האקטואליסטית לסטטיסטיקה

כעת יכול האקטואליסט לטעון שגם הסטטיסטיקה שבה השתמשנו בהוכחה הזאת אינה אומרת מאומה על העולם. הרי הטיעון שהוצג כאן מבוסס על התפיסה האינפורמטיביסטית, שלפיה הסטטיסטיקה אומרת משהו על העולם, ולא רק על השאלה איך אנחנו רואים אותו. לכאורה הטיעון הזה מניח את המבוקש.

אך טענה זו אינה יכולה להיטען גם על ידי אקטואליסטים. נקדים ונאמר שאכן את הספקן הגמור אי-אפשר להזיז מעמדה זו בשום מקרה, אבל אקטואליזם אינו ספקנות. לדוגמה, את העובדות שבהן אנחנו צופים ישירות הוא כן מקבל כתקפות. הוא אינו מטיל ספק בראייה או בשמיעה שלנו. ובוודאי שהוא אינו מטיל ספק במתמטיקה או בלוגיקה. הבעיה שלו היא אך ורק עם הכללות מדעיות ועם יֵשים תיאורטיים.

כעת לעצם הטיעון. ראשית, קשה לראות מישהו שאינו מקבל את הסטטיסטיקה כטענה על העולם ועל התנהגותו. הסטטיסטיקה אינה הכללה מדעית ואינה כוללת יֵשים תיאורטיים. זוהי הנחה שמקובלת על כל אדם רציונלי. גם האקטואליסט יסכים שהוספת תפוזים לסל מתוארת על ידי חוקי האריתמטיקה, אף שהטענה הזו היא טענה בפיסיקה.

אבל יתרה מזאת, גם אם הסטטיסטיקה אינה טוענת מאומה על העולם, הרי גם האקטואליסט מסכים שהיא כלי עבודה מדעי חשוב, ולפחות הוא מסכים לכך שברמה המתודולוגית היא זו שצריכה להנחות אותנו כיצד עלינו לנהוג ולהסיק מסקנות (כבר ראינו שאין הבדל מתודולוגי בין האקטואליזם לאינפורמטיביזם). אך העוקץ של הטיעון שהוצג כאן הוא שהבעיה ה”פילוסופית” המטא-מדעית הזאת מוכרעת בכלים מדעיים. השיקול הסטטיסטי, גם אם הוא רק מתודולוגי בעיני האקטואליסט, מכתיב לנו את המסקנה המטא-מדעית שחוקי המדע הם אמיתיים ולא רק נוחים. ומזווית אחרת, לכל הפחות נוכל להסיק מהטיעון האקטואליסטי שהוצג כאן, שאנחנו כחוקרים, או כבני אדם, לא היינו אמורים לתת אמון בחוקי המדע באשר לעתיד. גם אם המסקנה הזאת עוסקת רק בנו, ההנחיה שלה היא ההנחיה המדעית המתבקשת, וככזו היא מקובלת גם על האקטואליסט. אך האם אקטואליסטים אינם טסים במטוסים? האם הם אינם תופסים את חוקי המדע כאילו הם מנבאים היטב את המציאות (אלא רק מתארים את העבר, כלומר, מסכמים את מכלול העובדות הידועות)? ודאי שלא. לצורך הפרכת התזה של האקטואליסט, די לנו בכך.

ההצדקה הפילוסופית של האינפורמטיביזם

גם לאחר שהוכחנו אמפירית את העמדה האינפורמטיביסטית, הקושי הפילוסופי שעליו הצבענו למעלה בעינו עומד. כיצד אפשר להסביר את העובדה שהכללות אפריוריות אשר נעשות שרירותית (כלומר בוחרות בצורה שאינה אמפירית בהכללה אחת מתוך אינסוף צורות או הכללות אפשריות) אכן מצליחות במקרים רבים לנבא תוצאות של ניסויים? לכאורה העובדות האמפיריות הפרטניות שנאספות באמצעות תצפית ישירה (בדוגמה הקודמת אלו הן חמש המדידות הראשונות) אינן יכולות לשמש הצדקה להכללה שבה בחרנו. כפי שראינו, יש עוד אינספור הכללות שכולן תואמות לאותו מכלול של עובדות (כמו הקו המקווקו בגרף שלמעלה), ואנו דוחים אותן משיקולים אפריוריים ולא אמפיריים. זוהי בעצם “בעיית האינדוקציה” של יוּם: מהי ההצדקה להכללות המדעיות שאנחנו מבצעים? כפי שכבר הזכרנו למעלה, זוהי למעשה בבואה של הבעיה הקאנטיאנית של הסינתטי-אפריורי: כיצד אנו יכולים לטעון טענות סינתטיות באמצעים אפריוריים? כאמור, המתודה הטרנסצנדנטלית הקאנטיאנית אינה מציעה פתרון משכנע לבעיה זו.

אלא שהפעם אנחנו כבר ניצבים לפני עובדה, ולא לפני מוטיבציה רציונליסטית גרידא. כפי שראינו, היכולת שלנו לבצע הכללות מוצדקות (אף שלא הכרחיות) היא עובדה סטטיסטית. אנו רואים באופן אמפירי חד-משמעי את המדע מתקדם, ומתוך כך מאשרים את האינפורמטיביזם, ולכן אי-אפשר להתעלם מן העובדה הזאת. כעת לא נותר לנו אלא לחפש הצדקה תיאורטית לעובדה זו, ולא לשאול את עצמנו אם היא אכן נכונה. השאלה שעמה עלינו להתמודד אינה השאלה אם האינפורמטיביזם צודק, או שמא האקטואליזם. השאלה היא כיצד זה קורה שהאינפורמטיביזם באמת עובד?[12] הבריחה אל האקטואליזם (שכפי שהסברנו למעלה, היא עצמה תוצאה של הבעייתיות הזאת) כבר אינה חלופה אפשרית, שכן היא מופרכת אמפירית, כפי שראינו כעת.

בספרַי שתי עגלות ואת אשר ישנו ואשר איננו הראיתי כי הדרך היחידה שאפשר להסביר באמצעותה את העובדה המפתיעה הזאת היא הדרך ההוסרליאנית של “ראייה אידיתית” (התבוננות באידיאות). נראה בעליל כי יש לאדם יכולת להבחין בחוקי הטבע ישירות. שלא כמו האמונה הרווחת, ההכללה כנראה אינה באמת הליך אפריורי, כלומר היסק שנעשה כולו בחשיבה, אלא הליך הכרתי, או ליתר דיוק, הליך שיש לו רכיבים הכרתיים. כאשר אנו צופים בחמש התוצאות הניסיוניות שמתוארות בגרף שלמעלה, אנו לא רק מודדים חמישה ערכי תאוצה פרטיים, אלא מצליחים “לראות” דרך הניסיונות הפרטניים הללו את החוק הכללי שמשתקף בהם. בניסוח של אדמונד הוסרל נאמר כי הניסויים הפרטיים הם “שקופים” בעבורנו, ודרכם אנו מבחינים בחוק הכללי שעומד ביסודם, כלומר בהכללה הנכונה, ויכולים לבחור אותה שלא באקראי מתוך אינספור ההכללות האחרות. האינטואיציה שלנו מורה לנו כיצד להכליל נכון. האינטואיציה אינה כושר של החשיבה בלבד, אלא גם של ההכרה. אין לנו מנוס מהמסקנה שההכללות הן תוצר של הכרה אמפירית ולא רק של חשיבה אפריורית. השכל שלנו רואה את התוצאה, ולא רק חושב אותה.

גם אם הקביעה הזאת נשמעת מיסטית משהו, קשה להכחיש אותה. האקטואליזם, אשר מניח שלאדם אין יכולת כזו, ולכן מסרב לראות בתיאוריה תוכן עובדתי נוסף על מכלול העובדות הפרטניות שמהוות את הבסיס האמפירי שלה, הוא עמדה שגויה. עמדה זו הולכת ומופרכת כל הזמן, הפרכה אמפירית, לאורך כל התהליך המדעי.

האדם הרציונלי, להבדיל מן הרציונליסט, אמור להכיר קודם כל בעובדות, ללא תלות באופיין, ורק לאחר מכן לחפש להן הסבר סביר. הכחשת עובדות אך ורק משום שהן נשמעות מיסטיות היא אולי עמדה רציונליסטית, אך בהחלט לא רציונלית. במקרה שלנו היא אינה עומדת במבחן המציאות האמפירית.

סיכום: בחזרה לעקרון התער של אוקהאם

המסקנה מדברינו היא שלעומת מה שמקובל לחשוב, כל אחת משתי העמדות בשאלה האקטואליסטית-אינפורמטיביסטית אינה היפותזה פילוסופית גרידא, אלא טענה שיש לה תוכן אמפירי. יתר על כן, ראינו שהדילמה האקטואליסטית-אינפורמטיביסטית ניתנת להכרעה בכלים אמפיריים. עוד ראינו שהאקטואליזם הוא למעשה טענה שהופרכה, וממשיכה להיות מופרכת אמפירית אלפי פעמים במשך ההיסטוריה של המדע. כל ניסוי שהצליח אי-פעם עד כה הוא נדבך בהפרכה הסטטיסטית המתמשכת של העמדה האקטואליסטית. ועל אף כל זאת, משום מה לא מעט הוגים ממשיכים לאחוז בגישה זו, וגם מתנגדיהם בדרך כלל מתווכחים עמם במישור הפילוסופי ולא במישור האמפירי (ראו, לדוגמה, אצל בכלר). מאמרו של בנימין הוא דוגמה מצוינת לתופעה זו, שכן הוא מאמץ את התזה הסובייקטיבית לגבי עקרון התער כאילו היתה כאן שאלה פילוסופית גרידא, בעוד השאלה הזו הוכרעה וממשיכה להיות מוכרעת כל העת ברמה האמפירית.

כמה מסקנות עולות מכך. האחת, שהתיאוריות המדעיות הן טענות על העולם, כפי שטוען האינפורמטיביזם, ולא רק שפה יעילה ונוחה לשימושה של הקהילייה המדעית, כטענת האקטואליסטים.

כדי להבין את הקשר לנדון דידן, יש לשים לב שהקו הישר בשרטוט שמובא למעלה הוא תוצאת היישום של עקרון התער האוקהאמי. כפי שראינו יש אינספור אפשרויות להעביר קו דרך כל הנקודות שנמדדו בניסוי. מדוע אנחנו בוחרים את הקו הישר? כי הוא הפשוט ביותר. האם זה הכרחי? ודאי שלא. האם מדובר באמת “קיומית”? כאן הוכחנו שבהחלט לא. התער של אוקהאם חוזר ומתאשש לכל אורך ההיסטוריה של המדע ככלי ממעלה ראשונה להגיע אל האמת העובדתית. הפרשנויות הסובייקטיביסטיות שלו אינן עומדות במבחן הביקורת. כעת חובת הראיה עוברת להוקינג וחבריו.

[1] הארכנו בזה, ובאופן הפעולה שלמידות הדרש ההגיוניות בכלל, בספר מידות הדרש ההגיוניות: היסקים לא דדוקטיביים בתלמוד, מיכאל אברהם, דב גבאי ואורי שילד, לונדון 2010. ראה גם בשני מאמרינו בגיליונות בד”ד (23 ו-24).

[2] אמנם בסוגיית מכות ישנה מחלוקת תנאים בזה, אך בספרנו הנ”ל (ראה שם עמ’ 63, 121, ובעיקר בתחילת הפרק השישי) הסברנו שהמחלוקת הזו היא רק במקרים מיוחדים (כאשר הפירכות הן פירכות הלכתיות ולא עובדתיות), וביארנו שם גם את ההיגיון שבזה.

[3] אגב, מכוח אותה סמכות-על, בתחילת ספרו החדש הוקינג מכריז בפזיזות אופיינית על מותה של הפילוסופיה. על התופעה של אנשי מדע ידועים שנוטלים לעצמם סמכות לטעון טענות בפילוסופיה ונכשלים בצורה מביכה, עמדתי בהרחבה בספרי אלוהים משחק בקוביות.

[4] עמדתי על דוגמה נוספת לתופעה זו במאמרי ‘מהי חלות’, צהר ב.

[5] הטיעון פורסם לראשונה בספרי את אשר ישנו ואשר איננו, בית אל 2005. התמצית שלו שמובאת כאן מבוססת על נספח ב של ספרי אלוהים משחק בקוביות, ידיעות ספרים, 2011. בנימין הביא זאת ממאמר מידה טובה 97, תשס”ט, שם הוא מופיע בתמצית מצומצמת יותר.

[6] ראו זאב בכלר, שלוש מהפכות קופרניקניות, אוניברסיטת חיפה וזמורה-ביתן, חיפה 1999. הספר כולו מוקדש לתיאור ההיסטוריה של העימות האקטואליסטי-אינפורמטיביסטי. ככל שהבנתי מגעת, לכל אורך הספר בכלר אינו מציע טיעון קונקרטי נגד האקטואליזם, ואפילו אינו דן בבסיס הפילוסופי שלו. הוא מסתפק בתיאור היסטורי של תנודות המטוטלת הפילוסופית-מדעית הזאת, ונראה כי הנחתו היא שהתמונה המתקבלת עצמה די בה כדי לשכנע את הקורא באבסורד שבגישה האקטואליסטית.

בהמשך דבריי ארשה לעצמי להציג באופן כללי את טענותיהם וגישתם של האקטואליסטים והאינפורמטיביסטים, ללא ציטוט מקורות ספציפיים, שכן הדברים מופיעים בפירוט רב מאוד בספר זה.

[7] גם התיאור הזה הוא מעט נאיבי, שכן יש להגיע למסה קריטית של כישלונות לפני שמחליפים תיאוריה מדעית, ומובן שקשה מאוד להגדיר את הקריטריון הזה. אפשר תמיד להציל תיאוריות באמצעות הוספת הנחות ויֵשים אד-הוק, וגם לתוספות אלו ישנה מסה קריטית, עד שהמבנה התיאורטי (הפרדיגמה) קורס. לצרכינו כאן הפרטים האלה אינם חשובים.

[8] ראו על כך בספרו של הוגו ברגמן, מבוא לתורת ההכרה, פרק ט (“השכלנות של העולם”), שם הוא סוקר כמה וכמה תשובות שונות שניתנו לבעיה זו, ודוחה את כולן אחת לאחת. ראו גם בספרו הוגי הדור, בעיקר בהקדמה.

[9] הרחבתי על כך בהיבט הפילוסופי בספרי שתי עגלות וכדור פורח, בעיקר בחטיבה השנייה; ובהקשר המדעי ראו בספרי את אשר ישנו ואשר איננו.

[10] המושג “פשטות” גם הוא אינו חד-משמעי, ובכלר עוסק גם בכך.

[11] הוכחה פשוטה לכך היא תיאור של קו תיאורטי בצורה של פולינום ממעלה חמישית, אשר בו שישה מקדמים כפרמטרים. האילוץ שיקבע את ערכי המקדמים הוא שהפולינום יעבור דרך כל חמש התוצאות של הניסוי. אין ספק שישנם אינסוף פתרונות של שישיות מקדמים כאלו. אם נבחר פולינום ממעלה גבוהה יותר נקבל עוד אינסוף פתרונות.

לשיקול דומה, ראו לודוויג ויטגנשטיין, חקירות פילוסופיות, תרגמה: עדנה אולמן-מרגלית, מאגנס, ירושלים תשנ”ה, סעיפים 245-143, בסוגיית העקיבה אחרי כללים. ויטגנשטיין מראה שם באותה צורה מתמטית שישנן אינספור אפשרויות להמשיך כל סדרת מספרים נתונה, ולכל אחת מהן יהיה היגיון מתמטי משלה. אין המשך פשוט, או טבעי, במובן אובייקטיבי כלשהו.

[12] היפוך הניסוח הזה הוא קאנטיאני, ולא בכדי. קאנט הבהיר היטב שהוא אינו שואל אם אפשריים משפטים סינתטיים-אפריורי, אלא כיצד הם אפשריים.