“Painted in Words” – On Books, Paintings, and Early Cinema (Column 704)

With God’s help

Disclaimer: This post was translated from Hebrew using AI (ChatGPT 5 Thinking), so there may be inaccuracies or nuances lost. If something seems unclear, please refer to the Hebrew original or contact us for clarification.

Dedicated to my (I hope) friend, the painter Sam Bak,

with wishes for many more years of creativity and fruitfulness

I’ve just received an invitation to a launch evening for the painter Sam (Samuel) Bak’s memoir (memoir), titled Painted in Words, whose Hebrew translation was published less than a year ago (August 2024). Incidentally, anyone interested is invited to register and come.

As I’ll explain shortly, I feel a connection to the man and to his book, and so I thought it appropriate to dedicate a column in his honor.

Sam and the Trilogy

When the editing of my trilogy was completed, we (together with the editor, Chayuta Deutsch) considered what to do for the book covers. We searched online for relevant paintings or images, and didn’t really find something suitable. I no longer recall whether Sam Bak came to mind or whether I happened upon one of his paintings online by chance, but suddenly I remembered that already in my childhood my parents greatly admired the painter Samuel Bak. I recall that we even had a book of his paintings at home that, as a teenager, I loved very much (perhaps it was this one, though it was published when I was already fairly grown). I searched his work online and was once again amazed. Bak is an extraordinary painter, with stunning qualities. His paintings practically speak. They are very Jewish and deeply suffused with emotion. His world is broken and non-realistic, yet it manages to see and show life and dynamism among those silent shards.

Very quickly I realized I had found what my soul desired, and I began to look for a way to contact him to ask permission to use three of his paintings for the trilogy’s covers. A not-insignificant odyssey through various galleries in Israel eventually led me to Pucker Gallery in Boston, which represents Sam and handles permissions of this kind. They referred me to him and he graciously agreed. As a result we began corresponding by email on various topics (this continued afterwards as well, together with Chayuta, and from then on we call him “Sam”). He allowed me to choose any three paintings I wished and to use them (free of charge, in his great kindness).

I suggest you browse the collection of his paintings on the gallery’s site and generally online (he has thousands of works. He is extremely prolific and never stops painting; even at his advanced age he simply hasn’t stopped). You will surely see that my enthusiasm for these paintings is well-grounded (even if, of course, I am not entirely impartial).

The Rationale

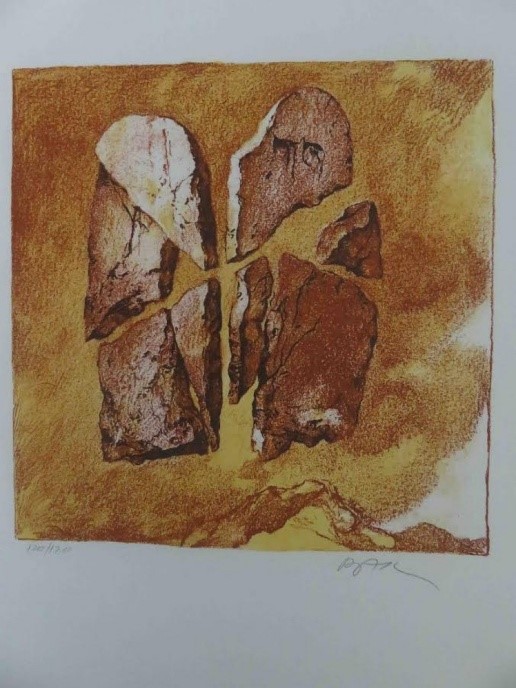

In the end, I chose three different paintings of the Tablets of the Covenant (he has several more of these). I’ll include here the appendix to my permission request, where I explain the rationale for using precisely these on the trilogy’s covers.

| Appendix: Cover Design of the Trilogy – Rationale

The trilogy is a structure of three books, each of which stands on its own (self-contained), yet together they create a complete framework of “lean” theology. The motivation for writing it is described in the trilogy’s introduction (printed at the beginning of each of the three books): the precarious state of Jewish tradition in our time. My diagnosis is that the root of the problem is that the picture of Jewish tradition today appears to be an anachronistic structure containing much “fat” that accumulated over the generations. Hence the proposed solution is to rebuild it from the ground up, in a leaner and more flexible way—faithful to the ancient source yet suited to the present. This is a somewhat ambitious aim, but it is the need of the hour and, in my view, of great significance for the continuation of our tradition. The result of this process is the following three books (whose writing and editing have now been completed): First Book: The First Existent — Faith, Religious Commitment, and Rational Thought This book discusses proofs for the existence of God and arguments for Jewish religious commitment. Second Book: No One Rules the Spirit — Toward a “Lean” and Updated Framework for Jewish Thought This book attempts to outline a lean, minimal framework: rejecting illogical and unnecessary additions that have turned into “articles of faith.” It argues for the absence of authority in doctrinal principles. Third Book: Walkers Among the Standers — On the Need and the Possibility of Refreshing Halakha This book deals with change and updating in Halakha, authority and autonomy, external values, tolerance and pluralism, and first-order versus second-order halakhic adjudication. In the search for a cover that would best express the spirit and significance of the books, and that would give them a worthy artistic and aesthetic dimension, and after much thought and consultation with various people, we (the editor, Dr. Chayuta Deutsch, and I) decided to choose three paintings by the Jewish painter Samuel Bak (a Jewish painter born in 1933 in Vilna, Lithuania; lived and created in Israel; and now in the USA), all three depicting the Tablets of the Covenant in different forms (though for him this is not a triptych but separate images around the same theme). When viewing the paintings, certain connotations and interpretations arose for us (of course, this is merely our perspective; other readings are possible), from which we understood that these three paintings are highly appropriate for reflecting the trilogy’s trajectory, as I’ll now explain:

The first painting contains an image of two broken tablets, with no inscription on them, and their form is not entirely clear. For us this expresses two aspects of the starting point: the problem—tablets that are broken and ancient (non-relevant); and the beginning of the solution—taking the minimal, primordial substrate, still somewhat “in the heavens,” a universal rather than a particular Jewish form (nothing written yet, though the shape of tablets already appears), and from it beginning to rebuild everything anew.

The second painting shows two tablets more consolidated in form, but bearing only the Divine Name at their top. There is no inscription, because “Jewish thought” is, in my view, an empty domain (I argue in the book that doctrinal principles, by definition, are universal). Yet on this plane, a Jewishness—or Jewish tradition—already begins to take shape, in the form of the Tablets. In the background there is smoke rising from a crematorium—part of our history. Beyond the physical and cultural destruction, this can express the rupture that occurred in Jewish thought, which in my estimation offers no framework within itself to account for such events (I discuss this as well in the second book). My claim is that from that rupture the contemporary tradition can and should emerge. Graphically, the blank tablets are themselves a kind of response to that rupture.

The third painting shows two tablets further consolidated, now already bearing an inscription (albeit sparse—the book deals with a “lean theology”). These tablets are composed of different elements, expressing the polyphony and the various influences that joined the Jewish tradition over the generations; together they constitute the structure of the present tablets, allowing for great complexity and flexibility. This entire tripartite structure stands as an alternative to a picture of monolithic, generic tablets that describe a uniform, intact structure—without fractures and without differing parts—upon which are inscribed ten agreed-upon, forceful, unequivocal statements that obligate everyone.

This contrast expresses what creates the problem, and the move from the generic tablets to the structure represented by the three paintings is the expression of the proposed solution described in the trilogy. It is worth noting that at the bottom of the third painting lies a trace of the two traditional tablets, while the larger, eclectic, polyphonic tablets replace them and take their place in the present. I believe this trilogy (ambitious in a certain sense, in that it seeks to present a complete, coherent structure of Judaism from the ground up—continuing what exists yet renewing and updating it) is of great significance for the continuation of Jewish tradition. I estimate that Bak’s three paintings will greatly contribute to its design and understanding. |

A Few Words About Sam

From Wikipedia one can gather that Sam lived a life full of upheavals, hardships, and adventures. He was a child in the Vilna ghetto, discovered already in his childhood by two friends, Avraham Sutzkever (later an Israel Prize laureate) and Shmerke Kaczerginski (journalist, poet, and partisan), two poets in the ghetto, both already adults. They saw in him an artist of exceptional talent even at a very young age. At nine he was already exhibiting his first show (there is a notebook with his drawings from that period, which serves as a framing motif for his memoir); he hid in a monastery, was sent to the ghetto and to a labor camp, returned to the monastery, then again Vilna, a DP camp, and then to the Land of Israel. His father was murdered at Ponary a few days before liberation from the Germans. Sam succeeded in reaching Israel, served in the army, moved to various countries, and for the last several decades has lived and worked in the USA. In Lithuania, Bak is considered almost a national painter, with museums dedicated to his work; conferences on him and his oeuvre are held around the world, and exhibitions of his works appear in galleries and museums worldwide. Universities offer courses on his work, and he himself lectures quite a bit worldwide. Sam is also well known at Yad Vashem here in Israel. A true polymath—anyone who looks at his paintings sees this immediately. In short, beyond the astounding artistic talent, the man is a walking slice of history.

In our conversations with him, Sam—now over ninety—came across as alert and sensitive, with a youthful spirit and a sense of humor, excellent English (at times hard for me to keep up with; he speaks fluent Hebrew, of course, but his computer is in English), and a broad education in many fields. Sam is well-versed in what’s happening in Israel and holds well-formed positions about us (often not exactly in my direction 😊). In those conversations, his autobiographical book came up repeatedly (a memoir accompanied by drawings) published in English in 2002 (Painted in Words: A Memoir), translated into German, Lithuanian, and other languages—but not into Hebrew. For decades he could not find a way to publish it in Hebrew, and it was clear that this pained him. At that point, the indefatigable Chayuta entered the picture and began an energetic effort to find funding and a publisher (I was somewhat involved at the start, but this is entirely her project). After years of work she succeeded in finding partners in the Association of Vilna Immigrants who took up the cause, and, as noted, in August 2024 the book was finally published in Hebrew by Kinneret-Zemora-Dvir.

The Nature of the Book: Early Cinema

As noted, the book’s title is “Painted in Words.” I don’t think there’s a more fitting description of the book’s character and essence. While reading, I felt that paintings stood before my eyes. Sam has an extraordinary ability to describe a situation in words and place it before us like a painting. It seems that even when he writes a book he is, in essence, a painter. It is almost a visual book—not only in its illustrated parts but also in its textual ones. I don’t think I’ve encountered another book that evoked this sensation in me so strongly (though I knew the author is a painter, so perhaps I am biased). I realized that this book is in some sense a form of early cinema: a set of images running before the eyes to create a dynamic flow—even if fragmented (as a memoir naturally is)—of life. It reminded me that in my childhood there were screenings for children using a projector that showed static images one after another to tell a story. We had such a projector at home, and its arrival was a real celebration. By “early cinema” here I mean what I call the ancient cinema—when it was still silent—but had already moved from projecting a series of static images to a dynamic sequence (first done by the Lumière brothers in 1895).

If his paintings practically speak (as I described above), it seems his texts are practically painted. The difference between text and painting—and between both of these and film—becomes very blurred with Sam. So, in his honor and in honor of the book and its nature, I’ll now add a short coda to this column touching on the phenomenon of early cinema itself. In the next column I’ll try to present things in a more systematic fashion.

On Early Cinema and Cinema

When we watch a film, we are not aware that it is actually a series of static images projected rapidly before our eyes, creating the sense of a dynamic movie. Just like animated films—except that there the images are drawings rather than photographs. Think of a computer mouse pointer or the screen of your phone. We see it moving across the screen, but in fact nothing there truly moves. When the pointer “moves,” what actually happens is that it’s turned off in one spot and turned on at the adjacent spot. Continuing from point to point creates the illusion of motion, as if the pointer is running across the screen.

Why can’t we create true motion of the pointer on the screen? Why must it be effected by adjacent turn-off/turn-on steps? Why can’t we produce a film in the strict sense—namely, a dynamic creation not composed of a set of frames? The reason is that, due to the structure of our cognition, we are bound to a static mode of perception. When we look at a moving car, we actually see it standing still at each instant at a different point. Our brain integrates all those images and constructs from them a film of the car’s motion—just like the pointer example. Because of this limitation in our perception, the perception of something dynamic can arise only by means of a series of static frames that create the illusion of motion. This limitation underlies a whole set of puzzles and paradoxes. It also shapes the structure of our mathematical thinking. I’ll address all of this in greater detail in the next column.

I’ll just add here that, in this sense, Sam’s book does something akin to early cinema. It takes a set of static images—painted in words—and that sequence creates a living, dynamic film. This is very hard to achieve by means of a set of images hung in a museum. His move to painting with words succeeds in doing what early cinema does, and—more so—what modern cinema does.

Yet I think there are times when a single painting or photograph succeeds in expressing dynamism. This happens when it’s clear that the image captured a single isolated instant from within a dynamic process. If, as a photographer, you capture such an image—or as a painter you manage to create such a painting—then you have succeeded in turning one static frame into an expression of an ongoing process. That is the reverse of what cinema does through a series of frames. It seems to me that at least some excellent works possess this quality of freezing a moment that doesn’t lose the dynamic dimension from which it was taken and to which it belongs. There is a back-and-forth relation between the static and the dynamic, and it can occur in paintings or in words, as well as in the intricate interplay between these two planes. Sam succeeds at both: in his text he creates a series of frames that become living dynamics, and in some of his paintings he captures moments that express the process from which they are drawn. The three paintings I chose for the trilogy attempt to combine these two directions and thereby help turn three books into a trilogy.

In the next column, as noted, I’ll try to examine more systematically the philosophical issue of the relation between dynamism and staticity.

Discover more from הרב מיכאל אברהם

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I feel this is also true for Tipax's songs like "The Old Station" and "Sitting in a Cafe" (and others). They too manage to capture a living reality within the lyrics. It's a genius of its own that I hardly know the likes of.

You wrote wonderfully and I”ll write some more thoughts about painting (the essence of capturing the dynamic within the static lies in the very pretension of painting; to simulate three-dimensional depth on a two-dimensional surface. The flat – if done correctly – gives an illusory depth to the viewer. A depth that is both in the physical and psychological sense). Regarding the projector of your childhood; a very strong description of this art and its implications – in Steven Spielberg's film The Fables – which actually talks about the director's life himself. It has some pearls about the artistic act. Happy Holidays

Beautiful, the paintings are truly special.