On Teleology and Causation in Science (Column 692)

With God’s help

Disclaimer: This post was translated from Hebrew using AI (ChatGPT 5 Thinking), so there may be inaccuracies or nuances lost. If something seems unclear, please refer to the Hebrew original or contact us for clarification.

In column 690 I mentioned the common description that the Western world of thought has moved from teleological thinking to causal thinking. According to this description, in antiquity religious thinking—which is fundamentally teleological (purpose-oriented)—reigned supreme. They tended to explain everything in terms of the end for which it exists (in religious thought it was implanted by the Creator). Even physical processes were explained by Aristotle on a purposive basis. Thus, for example, he claimed that a stone aspires to return to its place of origin (earth and soil) and therefore falls downward. In the modern era scientific thinking, which is causal in nature, took over. Within the modern scientific outlook, the stone does not fall “in order that something happen” or “because it aspires” to something, but “because of something.”

I noted there that, in my view, this is a myth that is inaccurate, or at least partial. When I looked for a place to point readers to, I discovered to my surprise that I had not yet devoted a column to this (I referred to the First Mover at the end of the third conversation. I now recall there is also Appendix D in my book God Plays Dice). So I will take this opportunity to fill the gap. In a certain sense, this column continues the line of thought of that earlier one, since here too we will encounter an ignoring of facts whose purpose is to evade the deistic conclusion regarding the existence of God. Let me recall that in the previous column we encountered an ignoring of facts on the believing side (what I called “statements of faith”), so the ways of the world are of a piece.

On Causation and Purpose

Leibniz proposed a distinction between the principle of causality and the principle of sufficient reason. The principle of causality states that every event must have a cause. The principle of sufficient reason states that every event or phenomenon must have a reason. But the reason need not be a cause. One difference between a reason and a cause concerns the time axis. The principle of causality requires the cause to precede the effect, whereas the principle of sufficient reason (which demands reasons and not necessarily causes) also allows for a reason that appears after the thing it explains—for example, when we say that a given event happened for the sake of some end. In my book The Sciences of Freedom and in various articles I relied on this distinction to define free will. I argued there that determinism explains actions on the basis of prior causes. Free choice is an action that is not done by virtue of a cause but is done for a purpose/reason. A random or chance action is one that has neither a cause nor a purpose/reason (see also column 645 and more). What reason and cause share is that in both cases the event or action is not gratuitous. It does not occur for no reason at all. I also explained there that what a purpose-driven action (but without a cause) and a gratuitous action share is that both can fall under the heading “indeterminism” (since neither has a cause). And yet they are two different mechanisms, although many tend to mix them up.

Teleological Explanations

I already mentioned that Aristotle tended to explain physical processes in terms of ends. A stone falls to the ground “because it aspires” to return to its place of origin. Aristotle saw the final cause (embedded in the nature of things) as the primary cause that moves things in the world. This view was widespread in the Middle Ages and was then adopted by many thinkers and scientists. They tended to give explanations of physical processes in terms of goals and aims that physical objects “want” or “aspire” to achieve. The explanations were in terms of “in order to” or “for the sake of,” and not in terms of “because” or “due to.”

Beginning with Galileo Galilei and the rationalist philosophers (chiefly Spinoza), the causal view began to spread. Today it is common to think that modern physics shows that Aristotle’s theory is wrong not only in its contents but also—and perhaps chiefly—in this fundamental sense. Processes unfold causally and not teleologically; that is, events occur “because of” events that preceded them, not “for the sake of” something that will come afterward. This causal view is sometimes called “mechanistic,” since the physical process is presented as a mechanical consequence of something that preceded it (its cause).

And yet, to this day there is a sense that as we ascend the ladder of the sciences—from the physics and chemistry of the inanimate, where it is common to think that explanations are causal (see below), toward the biology of animals and humans, and then to psychology, sociology, and the social sciences—the scientific explanations (?!) become more teleological and less causal. In biology, it is still customary today to explain the functioning of our organs by their purposes. The kidney, for example, is intended to purify the blood. Its existence is explained by its goal: purifying the blood. In psychology, we explain a person’s action by the goals he wishes to achieve. The person acts as he does “in order to” gain honor, to frighten, to ingratiate, to repress, to evade, and the like. All the more so in the social sciences (sociology and anthropology, political science, and to a certain extent even history).

In what follows I will show that the picture described thus far is, to a large extent, a myth. This myth reflects a certain misunderstanding of Aristotelian science and a lack of awareness of the import of many results of modern physics.

Teleology as a Manner of Formulation

According to this myth, in our contemporary scientific conception, teleological explanations at best say nothing, and at worst are simply wrong. Sometimes you will hear a “partial concession,” namely an admission that in some cases there really are teleological explanations in science (i.e., those that focus on purposes rather than causes), but this admission is immediately accompanied by the declaration that this is, of course, “just an anecdote.” The real explanation is the causal one, and teleology—the study of purposes—is merely another manner of formulation or reference to the same thing.[1]

The scientific trend today is to opt for causality and abandon purposiveness—teleology. A salient example of this process is the theory of evolution, whose main thrust is the inversion of teleological descriptions into causal descriptions. For instance, the bacterium’s flagellum (a kind of propeller that a bacterium uses to move through a fluid, as does a sperm cell advancing toward the ovum it will fertilize) is described in teleological terms as something “meant” to bring the bacterium to the food. But in evolutionary theory this is translated into a causal explanation: the flagellum is not “meant to” but “arose from” or “is driven by.” We succeed in describing the emergence of the flagellum, as well as its mode of operation, in causal terms (chemistry and physics) without resorting to the question of what it was made for, what it strives toward, or what its purpose is. Thus we can claim that the complex and seemingly purposive structures we see in the world around us are not truly purposive, but only appear so. In fact, they are products of a causal process produced by evolution. They have antecedent factors first, and only then aims.

Likewise, an animal’s defensive mechanism—explained as a means intended to protect it—is, in evolutionary translation, rendered as a causal description. How and why did this defense mechanism arise? Simply: only that animal which developed this defense mechanism survived. I note that Lamarckism, a different shade of evolutionary theory that preceded Darwin, was rejected precisely because it was based on teleological processes rather than causal ones. Darwinian evolution explains that the apparent purposiveness is but an imaginary veil for causal processes as described above.

As I mentioned, human language is usually teleological. In many cases I say I do something “because of” one matter or another. But in other cases I say I do it “in order to” achieve some goal. People act purposively. In contemporary scientific conceptions it is customary to say that this too is merely a mode of expression or even an illusion we have. In fact, we too do things “because” and not “in order to,” even if our subjective feeling is that we do them for some purpose. This of course touches on choice and determinism, a topic I will not enter into here.

Two Meanings of Teleology

When Aristotle said that the stone “aspires” to return to its place of origin, I assume he did not mean that it has a will to do so, and certainly not that it has the possibility of deciding not to do so. Aristotle too presumably understood that the stone does not decide of its free will, since such a choice (if we in fact believe in free will and choice at all) is a property of the human spirit alone. I allow myself to assume he did not even think the stone has consciousness (let alone choice). Aristotle’s use of teleological terminology for processes in the inanimate means only that their behavior can be described in terms of purposes rather than causes. The stone indeed has no choice but to “return to its place of origin,” yet still it is convenient and correct in Aristotle’s view to describe its motion downward in the language of “in order to,” and not in the language of “because of.” We must understand that the teleological description of the stone’s motion is deterministic and mechanical as well, except that its character differs from that of a causal description in that it faces the future rather than the past.

Note well: the strong aversion to Aristotle’s mode of thought rests on the claim that he anthropomorphizes the stone and inanimate objects. But that is a mistaken argument. Aristotle never dreamed of attributing desires and choice to a stone. We are dealing with a different manner of describing its mechanistic behavior, and therefore there is ostensibly no need to recoil from such descriptions.

Thus the teleological description of the inanimate in Aristotelian science is not truly purposive in the substantive sense. It is causality in disguise. Our description is teleological, but there is neither consciousness nor will and choice. Below I will show that the reverse process occurs in modern science.

The Modern Scientific Aversion to Teleological Explanations

Seemingly the teleological descriptions of Aristotle, whether right or wrong, were shown by modern science to be wrong. But that is not accurate. First, even today nothing prevents us from saying that a stone falls because it aspires to return to its place of origin. Since Newton we have a mathematical description of the stone’s motion, but whether it operates in a causal way (because of gravitational force) or in a teleological way (to return to its place of origin) is a matter of interpretation. In both cases we are dealing with a wholly deterministic occurrence.

So why do we insist on causal explanations? Why is there a sense that modern science has rid itself of Aristotle’s ancient teleology? Is it merely a change in manner of formulation or of interpretation?

The causal insistence is all the more puzzling if we recall that in most cases equations in physics state only a correlation (fit), or an equivalence (equal value), but not a causal relation. When Newton’s second law states a direct relation between the force acting on a body and its acceleration, there is not even a hint there as to which is the cause and which the effect. It is simply an equivalence between force and acceleration. One can write the equation with the sides swapped and nothing changes. One can write F = ma or ma = F. The equation does not “know” what is written on its right side and what on its left. We must understand that modern science does not speak the language of purposes, but neither does it speak the language of causes. It speaks the language of equations, and their causal reading is at most our possible interpretation (on the philosophical level) but certainly not a scientific finding. It is we who interpret Newton’s second law such that one side of the equation (force) is the cause and the other side (acceleration) is the effect. There is not even the faintest hint of that in the equation itself.

To sharpen this further, let us think for a moment of two massive bodies at a certain distance from each other. According to Newton’s law of gravitation they exert force on each other. Newton’s equation sets a relation between the force (and the acceleration it generates) and the magnitudes of the masses and the distance between them. But again the equation here sets a simultaneous relation; that is, the values of the masses and the distance at a given moment determine the values of the force and acceleration at that same moment. It is hard to see one as the cause and the other as the effect. From Newton’s equation’s point of view, the force could equally be the cause of the values of the masses and the distance.

In field theory, however, which is a more modern and sophisticated presentation of mechanics, the situation changes. There one does not accept action at a distance, and so one describes the development of the force over time. The force field propagates from each mass toward the other, and after (a very short) time it arrives and acts on them. Here the simultaneity of the equation is broken, and the masses precede the action of the force in time. Seemingly here it is already natural to see the masses as the cause and the force as the effect, since it appears later. But that too is not accurate, for temporal precedence still does not determine causality. I have explained more than once that a causal relation contains three components: temporal precedence (the cause precedes the effect), logical conditioning (if the cause occurs then the effect occurs), and production (because of the cause the effect occurs).[2] Therefore, even if we see temporal precedence and logical conditioning in the equations, the causal interpretation remains philosophical (we decide that the masses cause the emergence and operation of the force, i.e., there is production as well). It does not arise from the equations themselves. I already noted that David Hume argued that causality is nothing more than logical conditioning and has no dimension of production.

But this is only the beginning of the problem. We will now see that even at the level of description, modern physics is not truly causal.

Translating a Causal Explanation into a Teleological One and Vice Versa

Many teleological explanations can be “translated” from the language of purpose to the language of cause, and vice versa. A person reaches for the phone not in order to speak with his friend, but because there was within him a desire to speak with his friend. The desire to speak, which is a prior occurrence, is what caused the reaching for the device. Thus one can see this explanation as causal rather than teleological.

Before I continue, I must note that this is not precise. It is important to understand that this mode as well does not fit the behavior of a material being (what caused the desire?). One may say that desire in its essence is the inversion of a purpose into a cause. If so, the statement that what caused me to make the phone call was my desire to speak does not solve the principled problem. The question is how desire turns purpose into cause, and whether such a thing can be done by and within a material being. There is no real translation of purpose into cause and vice versa. The emergence of desire is teleological, and the operation of desire and the unfolding of its results are causal. These are two successive stages. But I will not enter into all this here (my book The Sciences of Freedom is devoted to it), for we are dealing with the inanimate.

At the end of the eighteenth century, for a short time, teleological explanations burst stormily into physics. As I noted, Newtonian and Galilean mechanics are causal in nature. There are forces that cause the acceleration of the body on which they act. Motion is the result of the action of a force on the body, not the realization of an “aspiration” for something. But Lagrange, an Italian-born French mathematician and astronomer (1736–1813), developed an alternative formulation of Newtonian mechanics in which, instead of describing forces that cause acceleration, one uses action functionals.[3] These are functionals of position and time, from which one can extract the path of motion via mathematical considerations of minimizing these functionals. The path traversed by a body is the one that makes the action functional take a minimal value. Hence these are sometimes called “principles of least action.”

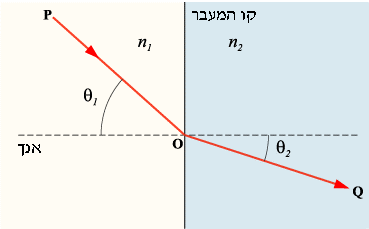

The best-known and simplest example of such a principle is Pierre de Fermat’s principle in optics (Fermat’s principle). Geometrical optics deals with the description of the straight-line motion of light rays. It turns out that when such a light ray passes from one medium to another—for example, when a light ray passes from air to water—its line of advance breaks (see the diagram below).[4] The law describing the relation between the angles of refraction is “Snell’s law.” This is the “causal” description of this process. If the angle of incidence of the ray on the boundary line—i.e., the angle at which it strikes the transition between air and water—is given, we can compute from it, using Snell’s law, the exit angle of the ray into the water. In this view we are dealing with a causal process, since the ray’s impact on the water and the different character of the medium it strikes (water) compared to the medium from which it arrives (air) “cause” the light ray to deviate from its path.

Refraction of a light ray, described by Snell’s law. n denotes the refractive indices (by how much the speed of light in that medium is smaller than the speed of light in vacuum) in water and in air. The angles of incidence and exit are denoted by θ. The exit point of the ray is P, and Q is the endpoint of the path.

Fermat showed that one can offer a teleological description of that very process, by means of least action. Fermat’s principle states that a light ray will always travel between two given points along the path for which its travel time is shortest. The customary way to illustrate this is to think of a situation in which a lifeguard standing at point P sees a person drowning at point Q and of course wishes to traverse the distance between the two points as quickly as possible. Clearly he must run along the shore and then swim in the sea, and clearly his running speed is higher than his swimming speed in the water. Therefore, it is not right for him to go along the straight line connecting the two points; rather, it is better to move along a path that is as long as possible on land and as short as possible in water. On the other hand, lengthening the land segment lengthens the entire path, and perhaps also the arrival time (the straight line between P and Q is the shortest distance). It turns out that the path along which the lifeguard ought to run is a straight line that breaks at the waterline, exactly like the red line in the picture above. The refraction angle naturally depends on the ratio between running and swimming speeds. The faster the running relative to the swimming, the angle will adjust so that the land segment is longer, such that the arrival time is minimal (the speeds are represented by the refractive indices n of the light).

Fermat’s principle states that a light ray that “wishes” to move between these two points will move along the same path as the lifeguard, and the angle will be determined according to the ratio between its speed in air and its speed in water (which is lower). Its path will be broken, as we saw for the lifeguard. Thus the relation between the angles of motion in the two regions, set in geometrical optics by Snell’s law, can be determined by computing the path that yields minimal travel time. In this case, the time required to traverse the path is itself the action functional of the problem, and its minimum determines the path. Fermat’s principle is an extremely simple description that encompasses the entire set of laws of geometrical optics (Snell’s law, the laws of reflection, and so on).

It is important to understand that Fermat’s description is teleological, since the motion of light is described in terms of “choosing” the shortest-time path. Again, this does not mean that light truly “chooses,” or that it has the option to decide to move more slowly or along another path, but that its mechanical and fixed motion is described in terms of purposes rather than causes. It moves at those angles “in order to” (minimize time), and not “because” (refraction created by striking the boundary between air and water). As described above, there is also a causal description of light’s motion, i.e., the ordinary laws of geometrical optics. One can prove that this causal description is mathematically equivalent to the purposive description. Every path obtained by computation via the causal formulation will be identical to the path obtained by computation via Fermat’s principle of least action (time, in this example).

Lagrange proposed a similar teleological description for all the laws of mechanics (this is what is called “analytical mechanics”). Instead of speaking the Newtonian language that deals with forces that move and accelerate bodies, we speak of bodies that “choose” paths along which the action functional takes a minimal value. In this case the function is not time but another quantity called the Lagrangian or the Hamiltonian (there are several possible formulations), and it is related in various ways to the energy of the body (imprecisely put: the chosen path is the one that minimizes energy).

The teleological flowering in physics was temporary and brief; immediately thereafter this current sank back into oblivion. At least in terms of consciousness, causality returned to rule physics with a strong hand from then until our day. Ask physicists and they will tell you it is a mathematical anecdote and nothing more. The truth is that the laws are causal, but mathematics allows, at least in some cases, the presentation of an equivalent teleological description that yields the same results. Certainly interesting, but not essential.

Which of the Two Formulations Is More “Correct”?

It is important to understand that the question of which formulation is more physically “correct” has no scientific meaning, for at the scientific level they are wholly equivalent. But that does not mean the question is meaningless. It certainly has philosophical meaning. The philosopher can wonder which of them is more correct. The choice between the two is a function of worldview, and I will return to this below. This is unlike the Copernican question—does the earth revolve around the sun or vice versa—which is a question utterly meaningless even at the philosophical level. There we are certainly dealing with two equivalent modes of description, and the difference between them is only where we decide to pin the origin of our coordinate system (see about this here, in column 481 and more).

How can we approach the philosophical question and form a position about it? As we saw in the example of Fermat’s principle, the teleological explanation is simpler and more general, for it is a single general principle that explains all of geometrical optics. By contrast, the causal description is more complex and complicated, since it consists of a collection of several laws that have no direct connection to each other. For some reason, it is precisely the more complex explanation—the causal one—that wins the reputation of being the true one, and the simpler explanation—the teleological one—seems to many to be a mathematical curiosity.

The examples from evolutionary theory mentioned above are, ostensibly, examples of the same type. Evolution offers a causal description for what manifestly appears purposive. We saw that the operation of the flagellum that moves the sperm toward the ovum is described as a process of cause and effect, and this description is presented as an alternative to the teleological-purposive explanation. Yet, as we saw there, in the philosophical sense this is not truly an alternative. For the entire process still demands elucidation. How does a blind process assemble stages one after another in a way that creates a well-designed, complex, and manifestly purposive enterprise? We saw that, at least at the philosophical level, teleology must accompany causal explanations. When we describe the activity of the engineer who set (or legislated) the laws, he presumably acted by purposive considerations. Once the laws were created, they have a causal impact on reality.

However, unlike in the case of optics, in the biological context, at least at the scientific level, the causal explanation is fuller and more comprehensive, since it offers detailed mechanisms and provides us with predictions for occurrences in other circumstances. The teleological explanation in this case is merely a slogan (the bacterium advances toward the crumb “because” it wants to eat it. There is no explanation or detail here, merely a bare assertion). Thus it seems that causality has pushed teleology to the margins in biology. One may say that we are dealing with two explanatory planes that do not contradict each other. Mechanism is driven by purpose, and the causal mechanism describes the manner in which the goal and purpose are put into effect. This is the explanation of how the designer and initiator of the enterprise builds it step by step. We describe the development of these stages according to the laws that the designer himself set. Hence, at the philosophical level—the only level relevant to the choice between two equivalent kinds of explanation—it is not reasonable to relinquish the teleological aspects of the process even in the case of the flagellum. But in physics we will see shortly that the situation is even more clear-cut. It turns out that precisely in physics, the science of inanimate matter—the very one seemingly immersed deepest in the causal domain—there are more and more areas in which there is no causal alternative at all, and the teleological description is the only one present in the arena (and not merely as the simpler explanation, as in the case of optics). This is a decisive consideration in favor of teleology, for now we no longer truly have two alternatives to choose between. In physics, the truth is that there is only one.

Force and Potential: Classical and Modern Physics

In classical mechanics we know two kinds of description for the motion of bodies. The Newtonian description uses forces that cause accelerations and motions. For example, when a ball lies on a slope, the earth exerts on it a force of attraction (gravity), and this force moves it downward. This is manifestly a causal description. However, alongside this description, every beginning student of mechanics knows the picture that describes motion by means of potentials (i.e., potential energy). The same ball moves downward “because” its potential energy at the lower point is lower than at the higher point, and it “aspires” to reach the point where the potential is minimal. This is a teleological description, for the ball, as it were, “chooses” (though it is of course compelled to do so) to move to the point at which it has the lowest potential. It moves “in order to” and not “because of.”

Many do not notice that the potential picture is a teleological description of Newtonian mechanics (even without Lagrange).[5] Of course, even here the picture is still entirely equivalent to the causal picture. The force can be computed from the potential, and the potential can also be computed from the force, and therefore we have here two equivalent explanations, and it seems that at least scientifically there is no way to decide which picture is more correct. Perhaps the question of correctness has no meaning in scientific language at all, since “correctness” in science means realized predictions, and that happens equally in both formulations.[6]

The phenomenon becomes even more pronounced as we proceed to modern physics. Mechanics is a relatively ancient field (a few hundred years, since Galileo and Newton), but quantum mechanics, developed in the twentieth century, and its more modern version, field theory (quantum and classical), can be presented only in a teleological description. The physical picture in these fields uses only potentials and not forces. In quantum theory and modern physics there is no natural use at all of the concept “force,” and it can be described only artificially and only for very specific cases.[7] As we have seen, the language of potentials is teleological, since the physical object is driven toward an end, unlike the description in the language of forces where it moves due to a cause. The conclusion is that quantum theory is teleological in an essential way and has no parallel causal formulation whatsoever.

Add to this the fact that physics today understands that quantum mechanics is the more fundamental, and that Newtonian mechanics is merely an approximate application of it to sufficiently large bodies. Moreover, at least in the reductionist picture of the world, the entirety of reality (chemistry, biology, and some would say psychology and sociology as well) is nothing but the application of mechanics (in the sense of forces and motions) to large and complex systems. We discover here that precisely in the last hundred years there has been a real retreat in the process of causal conceptions’ takeover of physics. Quietly and gradually teleology has been taking center stage in modern physics, and in the most basic cases we discover that there is no causal description at all. There is only a teleological description, and therefore we need not even ask which is more correct.

Now the claim that the teleological description is merely an anecdote begins to appear very puzzling. Of course, one can speculate that we have not yet found the equivalent causal explanation, but that it exists. But to attack the teleological worldview as irrational, and to cling fervently to the causal conception, sounds like baseless fanaticism. When we find the causal explanation we can talk; in the meantime the facts speak for teleology.

In the common description, the line dividing causal explanations from purposive explanations constantly moves from below (the inanimate) upward (to the living and the social). Little by little causality conquers even the “higher” domains. It turns out that precisely in the natural sciences of the inanimate, those “below,” there is a contrary development (toward teleology). And as noted, according to reductionism which grounds everything in physics, this undermines and subverts the causal conception of the scientific structure as a whole. Thus the myth—so prevalent among contemporary physicists and philosophers—of scientific progress from the purposive direction to the causal one is more a phenomenon of consciousness than of science. Perhaps one may say that more and more domains are gaining a causal explanation equivalent to teleological explanations. Still, the teleological explanation is neither refuted nor found false. It is true that in these domains there is no longer a necessity to accept teleology, and causality can be an alternative or complementary option. But as we saw, there are domains—the most fundamental ones—in which there is as yet not even a causal alternative.

Why the Aversion? Teleology and Faith

We have seen that the facts are that it is unclear to what extent there is any scientific difference at all between a causal explanation and a teleological one, and in most domains the question cannot be decided scientifically (because of the equivalence between the explanations). We also saw that there are domains in which only a teleological explanation exists. This raises the question: why, nevertheless, are scientists and philosophers so averse to teleological explanations? Why do they insist on claiming that teleology is an anecdote and causality is the correct explanation?

It seems the reason is that, even if Aristotle agrees that the stone itself cannot decide where to move, the fact that the description of its fall to the ground is teleological implies that there is presumably another agent who decided or set the stone’s purpose. Objects that move toward an end, even if they do so not by their own choice (and perhaps precisely because they are compelled), appear to be driven by an external agent. That external agent is what sets their end and compels them to move toward it. If the stone itself has neither consciousness nor choice, who sets the end and causes the stone to move toward it? If it is gravitational force, then we have returned to the causal explanation and there is no point in speaking of purposes. I think it is natural to identify that agent with God, and that may be the reason for the strong aversion to teleological explanations—even though, as we saw, they are wholly deterministic and mechanical.

From another angle one may say that a material occurrence is supposed to have a cause. An occurrence toward an end (“in order to” and not “because of”) is an occurrence without an efficient cause, and as such it contradicts the principle of causality (though I noted that this principle itself has no empirical source. It is our a priori belief). Therefore, even if we propose a purposive—albeit deterministic—description for some natural occurrence, still in the background it is clear that there must be some underlying cause. If it is not found in the nature of things, then it is the result of the action of some agent outside physics. Again, materialists do not like extra-physical agents (particularly if they are called “God”). A priori belief in causality replaces belief in God as the originator of reality, and the strong and inexplicable aversion to teleological explanations, in my opinion, reflects the atheistic-materialist worldview.

It is no wonder that teleology, even when it is merely a manner of description or explanation, is usually perceived as linked to non-materialist conceptions (i.e., dualist ones, which claim that the world contains matter and spirit), and perhaps even theistic ones (that believe in God). This is, in my opinion, one of the central reasons for the fierce war waged in recent generations against teleological explanations in all fields of science, and for seeing causal explanations as the only type worthy of the label “scientific explanation.” The clear sense is that this is not only a question of right or wrong, but an ideological battle.

We have thus returned to column 690. As we saw there, the desire to avoid belief in God pushes us to adopt non-necessary conceptions and to make unreasonable choices and cling to them as if they were Torah from Sinai, even accusing those who do not hold them of being primitive and outdated (this is the counterpart of “heretic” in the secular-scientific jargon).

A Note on Physical Determinism and the Principle of Causality

In closing, I must sharpen a point that I am sure will arise for readers. I am a great believer in the principle of causality. I ground on it the belief in God (the physico-theological argument), and I also do not accept arguments that depart from causality and am certainly disinclined to mysticism. Only now, in the previous column, I pointed out that divine involvement in the world is problematic in my eyes because it entails a departure from the principle of causality. In short, the principle of causality does not follow from observation but from an a priori insight, and yet it seems to me very correct. If so, ostensibly I too fall into the pit I described here, since I choose to adhere to the causal description and reject other descriptions.

But that conclusion is mistaken. Belief in the principle of causality and in scientific determinism does not mean the scientific description must be causal rather than teleological. We saw that teleology in physics does not depart from the determinism of science. It is only a different manner of describing the deterministic process. I indeed hold that the laws of science are deterministic, but their formulation can be teleological (I have no aversion to the statement that the Holy One sends the stone downward). Therefore, in my view, divine involvement is problematic since it always entails a breach of scientific determinism (even if not of a causal formulation of the laws). Moreover, I still think that everything must have a reason, causal or purposive, and therefore if there is a world there is presumably also a God who created it.

Note that the discussion in this column, which contrasted causation and purposiveness, did not touch on the question of determinism. On the contrary, precisely because both descriptions fit the scientific conception, the wonder as to why people are averse to purposive formulations arises all the more sharply. In my estimation, in the name of opposition to God they espouse causality and recoil from purposiveness. Whereas I, precisely in the name of causality (or sufficient reason), believe in God—though I doubt His involvement in the world (at least ongoing and not sporadic involvement).

[1] These matters, of course, touch at their core on the question of determinism, and I discussed this at length in my book The Sciences of Freedom.

[2] See in detail in my book The Sciences of Freedom, chapter five, and here on the site in column 459 (the entire series that follows it deals with the relation between causality and time).

[3] The more precise mathematical term is functionals. A regular function takes a number as input and outputs another number. A functional takes a function as input and outputs a number. For simplicity I ignored this distinction in the body of the text.

[4] The diagram is taken from Wikipedia.

[5] This claim is not so simple, since we are dealing with a local minimum. If in front of the body there is an elevation of the potential, after which there is a lower minimum, the body will not be able to pass the hill before it and will remain in place. The body is not free to choose its target point at will. But this is not a substantive limitation of the claim that we are dealing here with a picture teleological in character. The body strives to reach the global minimum point, but there is a barrier in its path that prevents it from reaching it. In quantum theory even this limitation is lifted, for the ball can pass through the potential barrier (this is what is called the tunneling effect).

[6] If we introduce friction, or what are called “non-conservative forces,” we will not have a simple description of mechanics by potentials, and we will be forced to speak of forces alone. But it is known in physics that frictions do not appear except at high temperature, whereas at absolute zero—when “pure” physics is relevant—there is no friction. Therefore, in truth, frictions are not basic natural phenomena for the purpose of our discussion.

I note that phenomena at temperatures different from zero, called “non-conservative” (of energy), are the result of a mathematical averaging of a quantity called the “partition function,” which itself is built from the combination of different states of the system at absolute zero (that is, by means of potential and energy, and not by means of forces), and therefore indirectly at the base of this phenomenon as well stands a teleological description.

[7] There is a well-known paper by Feynman that attempts to define force within the quantum picture. It is an artificial description that tries to derive force from the potential.

Discover more from הרב מיכאל אברהם

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Two minor corrections – At the beginning of the article, it says an instead of if and at the end, it says in parentheses ann instead of inen.

To the body of the article – In the debate with Aviv Franco, you explained that the principle of causality is not subject to the timeline at all, here you write that causality is yes and taste is no

Chen Chen. Will be corrected.

I never explained this. Not at Franco's or anywhere else.

Here you explicitly say that. Unless I'm not understanding something here

https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxsKahxAyc4usVk5ReXeadzhcPPvqVJ_4_?feature=shared

You did not understand. I said that we can talk about a causal relationship even in a world where there is no time. In a world where there is time, the effect will not appear before the cause.

[M”M's note: In addition to the end of the third conversation in the first volume and the fourth appendix in God plays dice, it should also be noted at the beginning of the words in What Is and What Is Not, pp. 215-219, (and as noted in these sources themselves).

It is also noteworthy that in your series of lessons on Mysticism (by the way, this series really does not seem to have been written down in posts or books (except for post 267, but it discusses a different aspect)) or Peshat-Darsh, you devote time to this topic in the context of parallel levels of explanation. etc. And I came only to serve as a minister.]

Could you please explain why quantum mechanics can only be represented in a teleological description?

I didn't understand this point.

Thanks

I explained. She uses potential, not force.

Even its very formulation is teleological. The wave function is determined by an equation that must be satisfied. It's not like an equation of motion in classical mechanics.

Regarding evolution, you write this: “How does a blind process put together steps one after another in a way that creates a well-planned, complex, and clearly purposeful enterprise?”

I didn't understand, there is no reason or purpose here, but in fact the one who survives is the one who fits the environment! The only claim that there is complexity here is that several processes had to run in parallel, but from your words it means that this is not the main point of the rejection.

Of course there is. On the surface it seems purposeful, and the evolutionary explanation offers a causal alternative.

I didn't understand what you were arguing about, and what you were trying to say.

There is a discussion of teleology in modern science as early as the book “That which is, that which is not” . The second book in the Quartet. How did you forget that….

Regarding Snell's Law, there is a really nice video by Veritarium about it:

You describe the movement of a body in the presence of a potential as striving to reach a region where the potential is lower. This region that generates the movement is in the future (“down the road”) and therefore the movement is purposive.

For the answer, the same phenomenon can be described as being pushed away from the region where the potential is higher. This region that generates the movement is in the past (“up the road”) and therefore the movement is actually causal.

Where are you pushed? To describe the movement, it is not enough to claim that it is pushed from its current location, but also where it will go. You cannot offer a causal description for this.

Consider, for example, a wall inclined at an angle whose upper part is a horizontal line. A ball is standing on this line. Will it roll straight down or sideways (which is also down in terms of height and potential)? If all you said was that it was pushed from above, then why does it “choose” the straight path (perpendicular to the upper line)? Because that ”down” is better for it than the other ”down” (rolling down the wall at some angle to the upper line). This is clearly teleological.

Of course, in the language of forces, there is an explanation for this: the gradient of the potential (which is the force) is directed precisely in the direction of the greatest slope.

Hello Rabbi Michael,

What causes the accumulation of potential energy of bodies in teleological language? (For example, how can Keplerian motion be described in terms of aspiration alone)

Thanks in advance.

For the accumulation of*

I didn't understand the question. And in general, "what causes" is a question from the causal world.

There are dynamics in which kinetic energy will become potential energy (as in the Kepler problem, harmonic oscillator, etc.). Is it possible to describe such a process in teleological terms?

(For example, in the Kepler problem I have difficulty seeing a point towards which the mass only aspires. Perhaps it both aspires and is forced to move away)

I don't understand the question. What is the connection between these descriptions, in my opinion? Most of the situations we know combine different energies (unless the force is not conservative). But every trajectory of any body under any force can be described as a minimum of a functional, and this is a teleological description. The trajectory of a harmonic oscillator or of a body in a two-body problem (Kepler) is no exception to this rule.

I meant to ask about the description using potentials only, before the description using the principle of least action. Mainly because of the Rabbi's comment in the opening paragraph:

“Many don't notice this, but the picture of potentials is a teleological description of Newtonian mechanics (even without Lagrange’)..”

That's why I wanted to ask whether a description using potentials is sufficient. In a description using simple physics only (before analytical mechanics), it seems to me that at least some causality must be added here.

I didn't mean to make it difficult for the Rabbi to argue about the principle of least action. Thank you and sorry for the lack of clarity.

I don't understand the question. In any case, there are non-conservative forces that cannot be described in the form of potential. Therefore?

The description of mechanics (without analytical mechanics) must include a causal component.

Hello!

A. You wrote: “Aristotle's teleological descriptions, whether true or false, have been proven incorrect by modern science. But this is not accurate. First, even today there is no reason to say that the stone falls because it strives to return to the quarry from which it was quarried.” Aristotle's explanations have been proven incorrect by science not only because of the transition between teleological thinking and causal thinking, but also because it is not an adequate description of reality. Any two bodies with mass are attracted to each other, and not just objects are attracted to the earth. Also, according to him, fire rises because the source of fire is above, which turns out to be incorrect because all hot air rises.

B. What you wrote about potential “The body strives to reach the point of absolute minimum but there is a barrier in its path that prevents it from reaching it” The same is true for the Aristotelian explanation of objects falling to the ground, which strive to return to their source, but when a stone is placed on a table with an obstacle in its path, one must give up its pure aspirations. (And it is not to say that it only strives to have a connection with the source of its quarry, and when it is placed on the table, it is connected by the table, because if so, why does it fall when you put a stone on a vertical wall? And I really tried to ask the stone itself what exactly it wants, but for some reason it did not want to answer me...)

C. Regarding the last comment. If I understood correctly, you are saying that the principle of causality assumes that there is a "reason" for everything, and this means that there is determinism and not causality, so we assume teleological determinism. I didn't understand, it is clear that the principle of causality also says that there is a reason for everything and also when we explain physics in teleological terms we still need a causal explanation of what causes the teleological behavior and we say it is from someone external who imposed the laws (=God) and as you wrote yourself. So it is not that we are replacing causality with teleology, but we are replacing physical causality (which themselves have a non-physical cause) with teleological determinism (which also has a non-physical causality).

Best regards.

A. Thanks for the update. I thought Aristotle also knew quantum theory.

B. Do you really expect an answer? Expect some reading comprehension.

C. The teleological picture negates the principle of causality, and replaces cause with taste (which is either causal or purposive). I explained that even if we deal with the taste of determinism in our eyes. Here too, you don't need a long school day to understand what I'm saying.

A. I don't know what you think, Tom. What you wrote is important, and it's not accurate at all.

C. I relied on someone who once wrote: “From another angle, one could say that a material occurrence is supposed to have a cause. Occurrence towards a purpose (“in order to” and not “because of”) is an occurrence without a causal cause, and as such it contradicts the principle of causality (although my own comment has no empirical source. This is our a priori belief). Therefore, even if we offer a purposive description, even if it is deterministic, for any natural occurrence, it is still clear to us in the background that some cause must be present. If it is not in the nature of things, then it is the result of the action of another factor outside of physics. Again, materialists do not like factors outside of physics (especially if they are called “God”). The a priori belief in causality replaces belief in God as the creator of reality, and the great and incomprehensible reluctance to teleological explanations, in my opinion, reflects the atheistic-materialist worldview. Therefore, your complaint is not against me, but against the philosopher who wrote these things.

A. What I wrote is accurate to the point, which is hard to say about your understanding.

Ad hominem arguments have never done it for me. I discuss arguments, not people or quotes.

Do you admit that the quote from https://mikyab.net/posts/91449/ says what I wrote? So are you contradicting yourself or not?