A Look at “Lesser-Evil” Considerations (Column 555)

With God’s help

Disclaimer: This post was translated from Hebrew using AI (ChatGPT 5 Thinking), so there may be inaccuracies or nuances lost. If something seems unclear, please refer to the Hebrew original or contact us for clarification.

In the most recent Torah portion of Vayeshev I spoke in the synagogue about “lesser-evil” considerations. This topic was discussed here on the site in column 189, where I distinguished between cases in which such considerations are appropriate and cases in which they are not (“the lesser evil” versus “the greater good at its worst”). In any case, I explained there that the claim that one should always take the lesser-evil path (which is almost the term’s literal meaning) is problematic. In this column I wanted to revisit the subject and spell it out in more detail. Applying any implications to our stormy times is the reader’s responsibility.

Reuben’s Proposal

In Parashat Vayeshev the Torah relates that Reuben suggested to the brothers that they throw Joseph into a pit (Genesis 37:17–27):

“The man said, ‘They have traveled on from here, for I heard them say: Let us go to Dothan.’ So Joseph went after his brothers and found them at Dothan. They saw him from afar, and before he came near them they plotted against him to kill him. They said to one another, ‘Here comes this dreamer! Now come, let us kill him and throw him into one of the pits; and we will say, A wild beast devoured him; then we shall see what will become of his dreams.’ Reuben heard and rescued him from their hands, and he said, ‘Let us not strike him mortally.’ And Reuben said to them, ‘Do not shed blood. Cast him into this pit that is in the wilderness, but lay no hand upon him’—in order to rescue him from their hand, to restore him to his father. And when Joseph came to his brothers, they stripped Joseph of his tunic, the coat of many colors that was upon him, and they took him and cast him into the pit; and the pit was empty, there was no water in it. Then they sat down to eat bread, and they lifted their eyes and saw: behold, a caravan of Ishmaelites was coming from Gilead, and their camels were bearing gum, balm, and ladanum, going to carry it down to Egypt. Judah said to his brothers, ‘What profit is there if we kill our brother and cover up his blood? Come, let us sell him to the Ishmaelites, and let our hand not be upon him, for he is our brother, our flesh.’ And his brothers listened.”

Reuben proposes to the brothers to throw Joseph into the pit rather than kill him. The verses state twice that he did so to rescue him from their hands. Thus, to save Joseph, Reuben chose the less-bad option under the circumstances—i.e., he made a “lesser-evil” calculation.

How do we know Reuben’s intentions? Rashi there (v. 22) comments:

“‘In order to rescue him’—The Holy Spirit testifies about Reuben that he said this only to save him, so that he would come back and lift him out from there. He said, ‘I am the firstborn and the greatest among them; the blame will be placed on me.’”

From the end of Rashi’s words it seems that Reuben’s concern was not the improper deed itself but his father’s rebuke and the blame that would be attached to him. In short, he too was apparently not such a great saint. In any case, he certainly made here a lesser-evil calculation in the circumstances (even if it was not done for pure moral reasons).

If we spell out his reasoning, three distinct options lay before him: to cooperate with the brothers, to fight them to the end and risk failure (or risk his father’s rebuke), or to persuade them to sell Joseph. Cooperation is off the table (for more or less altruistic reasons), for he decided to save Joseph. Two options remained; between them, the one he chose was the lesser evil.

Why was fighting perceived as worse? The chance of success was small, and the cost (moral or personal) of failure was very great and irreversible.

Lesser-Evil Considerations: A Logical View

At first glance this seems like a logically necessary conclusion. Clearly, between two bad options, one should choose the less bad. One can debate which is less bad, but once we have reached a conclusion on that question, the decision follows of itself. And yet, there is a strong intuition that it is not always right to choose the lesser evil—i.e., there are situations in which compromise is forbidden (see the columns cited above). How can that be?

I will now present several types of considerations that nevertheless manage to overcome that logical argument—some step outside it and some play within it.

A. Expected-Value Considerations

Take for example the dictum of Rabbi Ila’i (Moed Katan 17a):

“It was taught: Rabbi Ila’i says, if a person sees that his evil inclination is overpowering him, let him go to a place where he is not known, wear black and wrap himself in black, and do what his heart desires, and let him not desecrate the Name in public.”

This is a far-reaching allowance to commit a transgression. A person who sees his urge overpowering him and estimates that he will not overcome it faces two options: (1) fight to the end, with a high (or certain) chance of failure; (2) give in and do something less severe, for in a far-off place and in black clothing at least there will not be public desecration of God’s Name. Rabbi Ila’i recommends choosing the second option, though it involves sin, because it is the lesser evil. If he decides to fight he may fail, and the price will be very high. It is better to commit a small, certain transgression than to enter a situation of a possible (or certain) grave transgression.

Rashi there (and other Rishonim) cite two interpretations of this dictum:

“‘What his heart desires’—a transgression; and since no one there recognizes him, there will be no desecration of the Name. And our teacher said in the name of Rav Hai Gaon: ‘And let him do what his heart desires’—meaning: indeed, since he dresses in black, etc., I guarantee that from then on he will not desire the transgression.”

The first reading is as I presented. But Rav Hai Gaon explains that by adopting this course there is a chance he will overcome his urge and not sin at all. According to him there is no license to sin, but a recommendation on how to cope in order not to sin. The first reading is of course the straightforward sense (on Rav Hai’s reading the concluding clause, “and let him not desecrate the Name in public,” is unclear), and it seems Rav Hai preferred it because it seemed unacceptable to him that there could be a l’chatchilah license to commit a transgression.

Two further notes. One may ask whether such self-assessment is valid—i.e., if a person estimates that he will not succeed in overcoming the urge, may he rely on his assessment, or is that itself the counsel of the inclination? Perhaps if we do not permit him, he will not allow himself to fail and will overcome. One can also bring in the question of determinism (see the article Middah Tovah, Parashat Chayei Sarah, 5767): is there a situation in which a person is coerced by his inclination to sin, in the sense of “the evil inclination clothed me” (Ketubot 51b; Kiddushin 81b)? In my view this is not necessarily related here, since the question concerns the person’s subjective assessment whether he will overcome or not, and even in a non-deterministic world one may estimate that he will fail. There is more to discuss, but it is not directly our issue. For us it suffices to assume he may fail, and ask whether he may weigh the lesser evil—i.e., tally the two options and their harms and decide by expected benefit/loss.

Another question: do we in fact rule like Rabbi Ila’i? The Rif and the Rosh on Moed Katan write:

“We do not accept the view of Rabbi Ila’i; rather, even if his inclination overpowers him, he must set his mind aright, for we hold that everything is in the hands of Heaven except fear of Heaven.”

Maimonides also omits the dictum, and thus it is unsurprising that the author of the Shulchan Aruch omits it (he himself wrote that he followed the majority of those three authorities). By contrast, Tosafot in Megillah imply that the halakhah follows Rabbi Ila’i. In my article cited above I brought several decisors who quote Rabbi Ila’i as if accepted in halakhah, and I expressed puzzlement.

A seemingly similar principle appears in the Talmud (Kiddushin 21b–22a) regarding the beautiful captive woman:

“The Sages taught: ‘And you see among the captives’—at the time of captivity, a woman—even a married woman—‘a beautiful form.’ The Torah spoke only against the evil inclination. It is better that Israel eat the meat of animals at the point of death that have been ritually slaughtered than that they eat the meat of animals at the point of death that are carcasses.”

Here we find the principle that it is preferable to feed people meat of dying animals that has been slaughtered (disgusting but permitted) than carcasses (a more severe prohibition). It seems that “animals at the point of death” is not actually prohibited (only repulsive), so this is not a comparison between a small prohibition and a large one but between a repulsive act and a prohibition—where all agree the permitted act is preferable. Still, one must discuss this in light of the comparison to the beautiful captive, where there does seem to be a prohibition (relations with a gentile, though its precise source is not fully clear). In any case, the Talmud’s phrasing suggests that the comparison to the meat of dying animals concerns something repulsive rather than truly prohibited; meaning that with a true prohibition there may be no room for a lesser-evil calculus.

In Rabbi Ila’i’s case, however, one can argue differently, since the estimate that he will sin may be read as an uncertain estimate: he assesses that it is very likely he will sin. Expected-value reasoning then enters: if he confronts his inclination head-on, there is a high chance he will fail, and if he fails the transgression will be grave (and public desecration will be added). If, however, he will manage to cope (there is also a small chance of that), then we gain fully (no sin and no desecration). If he chooses to go far away, he will certainly commit a lesser sin (indeed, he might also cope there and succeed). Thus this is still consequentialist reasoning, but the outcome of each step is computed by expected value: (chance of failure × expected harm) + (chance of success × expected benefit), versus going away with a certain small loss.

This somewhat resembles (though it is not identical to) strategy calculations in game theory, where one chooses a minimax strategy (minimizing the maximal loss) or a maximin strategy (maximizing the minimal gain). Some games have a defined value when these coincide (the minimax theorem). There too, there are several possible outcomes, and one seeks a strategy that guarantees maximal gain or minimal loss.

The case of Hezekiah and the prophet Isaiah described in Berakhot is also seemingly an example of such reasoning. Hezekiah does not want to have a child because he foresaw that a wicked son would issue from him. Isaiah tells him that he must fulfill the commandment of procreation because that is his present duty, and not to enter the “hidden counsels of the Merciful One” (i.e., consequentialist calculations about his future son’s wickedness). One might have said that since he does not actually know how his son will turn out, he should not make such calculations because expected value considers both possibilities (that his “prophecy” is correct and that it is not).

This returns us to Reuben. I explained that he did not know whether he would succeed in fighting the brothers and saving Joseph. Therefore he also made an expected-value calculation—on the chance he would succeed or fail and the consequences of each. Since failure would mean Joseph’s death, a critical and irreversible outcome, he decided not to take the risk and to seek a sale. This is essentially a lesser-evil reasoning that computes benefits by expected value. In any case, this type remains consequentialist; thus such a decision does not contradict the logical “lesser evil” principle.

B. The Status of a Prohibited Action

But the common understanding of the Hezekiah episode is different. The commentators take it as a categorical statement that we must not engage in such calculations—even assuming the prophecy were certain, i.e., even if it were clear that his son would indeed be wicked. Isaiah says to him:

“What concern have you with the hidden matters of the Merciful One? What you have been commanded you must do; what is pleasing before the Holy One, blessed be He, let Him do.”

He is not making cost–benefit calculations but stating a categorical rule. Such an approach seemingly contradicts lesser-evil reasoning (the underlying assumption in their dialogue is that refraining from having a child is less severe than producing a wicked child—especially if he would be a wicked king of Israel). How does this fit the logical argument above? If option A is in fact better (or less bad) in its outcome, why not choose it?

It may be that where committing a present prohibition is involved, halakhah does not allow us to transgress, even if in the end the outcome would be lighter than the alternative. This view says that consequentialist reasoning is not always legitimate even when correct. One must take into account what stands before one now and not make calculations about the future.

It is natural to limit this to action prohibitions (as opposed to result-based prohibitions). If the current prohibition is halakhically defined as an action prohibition, there is no room to permit it on consequentialist grounds. Outcome calculations are relevant only to result-based prohibitions. Therefore the lesser-evil calculus—being consequentialist by definition—does not apply. Thus, for example, relations with a gentile or eating non-kosher meat are plainly action prohibitions; therefore the outcome does not determine but the action. Hence eating carcasses would not be accepted as a lesser evil vis-à-vis a graver prohibition (e.g., slaughtering on Shabbat). What was permitted there is eating meat of dying animals, which is repulsive but not forbidden. One might extend such an argument even to result-based prohibitions under the rubric of “What concern have you with the hidden counsels?”—if at present there is a prohibition before you, do not play clever and make outcome calculations. You do not transgress now; leave the accounts and outcomes to God. This inclines toward “better to sit and do nothing.” You act at each stage according to halakhah, and whatever comes, comes. Regarding the beautiful captive, it is an action prohibition (relations with a gentile), yet it is permitted on lesser-evil grounds. Perhaps wartime loss justifies even action prohibitions. There they do not say “What concern have you….” Although the comparison to dying-animal meat suggests it may not be a true prohibition.

This approach indeed does not play on the logical field described above; it seemingly breaks the logical argument: although option A yields better outcomes, we still prefer option B because A is a present prohibition, and we do not set aside such prohibitions for outcome considerations. The next approach plays within that logical argument.

C. The Measurement Horizon

In many cases—perhaps in all—one can translate the argument that rejects the lesser evil into an argument for the greater good in the long term. That is, sometimes what seems the lesser evil only looks that way because we are looking short-term. But in the long term that option produces worse outcomes.

For example, if I allow a person to go to a far-off place and “do what his heart desires,” perhaps I gain (with this individual and this act) the avoidance of public desecration in the short term, but I thereby open a door for many to sin in the future—even in cases where many of them could have overcome their inclination. When a person has legitimacy to decide that he “cannot overcome,” he may so decide even when he could have. Hence there is logic to rule categorically not to choose the lesser evil in such cases (i.e., not to go away, put on black, and do as he pleases) but to stay and struggle. In the long term the harms of that policy will be smaller. Thus, for example, the prohibition to shave during Chol HaMoed was instituted so that people would shave beforehand and not delay. This is a paradigmatic long-term consideration: in the short term, I am forbidden to shave and will look unkempt on the festival; but in the long term, since shaving is forbidden, people will prepare in advance and the overall result will be better.

The upshot is that in such situations we are deciding for the lesser evil—i.e., choosing the option whose outcomes are less bad—but the outcome calculation is made on a longer horizon. This is not a departure from the logical consideration introduced above.

Similar examples were brought in column 189. After discussing Rabbi Ila’i’s case I argued there that voting in elections for “the lesser-evil” parties may sometimes increase the evil of the result in the long term (since parties will not improve their ways and better parties will not enter the market). There I also drew a fundamental distinction between situations which justify a lesser-evil policy and those that do not (“the greater good at its worst” versus “the lesser evil”). My argument there is of type C here—long-term versus short-term.

Of course, when the outcome is critical and irreversible there is room for a short-term lesser-evil calculation even in such a situation (perhaps that is the case of the beautiful captive). And if there is a chance we will not reach the long term at all, long-term reasoning may be pointless. But that again becomes expected-value reasoning.

Let us now see a few examples, within which another mechanism that departs from lesser-evil considerations will appear.

Slaughtering for a Gravely Ill Person on Shabbat

In earlier columns (62, 358–359) I discussed slaughtering an animal on Shabbat for a dangerously ill patient who needs meat to recover. Is it preferable to give him non-kosher meat (a carcass, pork) that we already have, or to slaughter an animal and give him kosher meat?

The Ran invokes a quantity–quality distinction: it is preferable to slaughter, although slaughtering on Shabbat is more severe (liable to stoning) than eating non-kosher meat (a negative command), because with non-kosher meat he transgresses with every olive-bulk he eats, whereas slaughtering is one (albeit severe) prohibition. This is a comparison of outcome metrics; thus according to the Ran the decision follows a lesser-evil calculus. And even if other Rishonim disagree and hold that one act of slaughter is still more severe, the dispute is over where the lesser evil lies—number of prohibitions versus their severity—yet both sides are reasoning by the lesser evil.

Others rule it is better to give non-kosher meat rather than slaughter. Some follow prohibition quality rather than quantity (contra the Ran)—again a lesser-evil calculation. But some views seem not to decide by outcomes at all. For example, one rationale is that what we presently have at hand is non-kosher meat, whereas slaughtering is a prohibited act yet to be done. Therefore we must use what we have rather than slaughter, since there is no justification to commit an act of prohibition when not necessary. Simply put, this says that even if the outcome of eating non-kosher meat is worse (per the Ran), that is still what we must do because there is no license to commit a present transgression with our own hands. This clearly parallels type B above (“What concern have you…”). One can also see reasons akin to type C (long-term). The Ran himself may be explained that way: eating non-kosher meat, in the long run, entails more prohibitions, even if in the short term slaughter is more severe.

Considerations of Saving Life

In my articles on separating conjoined twins and on organ donation, I discussed expected-value considerations in life-and-death decisions. Consider a case where two conjoined twins are born sharing one heart, and the medical prognosis is that both will die within about a year. The only way out is a separation surgery in which the heart is given to one while the other is left to die. I showed that in the symmetric case (with no natural assignment of the heart to one, making the other parasitic or a pursuer), most decisors forbid the surgery, seeing it as murdering the second infant.

My starting point was that consequentialist reasoning requires performing the surgery. The decisors say that in order not to commit murder we leave both to die (including the one who would be “killed” by us). That makes no sense: the prohibition of murder aims to preserve life; it is not reasonable to harm life to avoid the murder prohibition. Those decisors apparently see murder as an action prohibition rather than an outcome-based one, essentially saying: “What concern have you with God’s hidden counsels?” Do what is commanded now and do not transgress; whatever will happen, will happen. They choose mechanism B above—present prohibitions are not overridden by future benefits.

That explanation is possible, but substantively it seems wrong to me. An individual surely may perform such an action to save himself. For example, a person stands on the tenth floor of a burning building and considers whether to jump. If he jumps, he takes his life in his hands—which is prohibited; if he does not jump, he will surely die. Jumping gives him some chance to be saved. Does anyone imagine forbidding him to jump because he is now committing a prohibition? It seems obvious that it is permitted (so write the decisors regarding entering a risky surgery to cure a certainly life-threatening illness; see e.g. Igrot Moshe, Yoreh De’ah III:36; Achi’ezer, Yoreh De’ah 16:6; source in Avodah Zarah 27b). If so, an individual is surely permitted to endanger himself to gain a chance of rescue; therefore a conjoined twin—were we to ask him—would surely tell us to hold a lottery, since that gives him a chance to live instead of certain death. It is not plausible that when he is an infant and cannot act, we as his guardians (or a court) would be forbidden to decide so for him. If I am right, then decisions about life may indeed involve consequentialist reasoning and lesser-evil calculations (maximizing life or minimizing loss of life), even though murder is in some respects an action prohibition (indirect modes of killing do in fact exempt the killer, though the outcome is achieved).

In my article on killing a thief I argued that it is permitted to kill a thief to save one’s property (if there is no other way), and one of the arguments there was also a calculation of future outcomes. If I refrain now from the grave prohibition of murder, that may look like the lesser evil (better to lose money than to kill), but such a halakhic policy produces a situation in which everyone’s property is hefker before a violent robber. The multiplicity of future minor harms can justify a present severe prohibition. I brought proofs to that type of argument—a long-term consequentialist consideration (type C above).

This brings me to a fourth type of consideration that can depart from lesser-evil reasoning.

D. Rights-Based Considerations

In the thief case one can present a further, distinct consideration. Even if we assume that the murder prohibition is more severe than the many future problems (the danger to all our property), there is still room to permit it for a different reason. The thief himself created the equation that places me in a dilemma between murder and monetary loss. The one who created the equation must bear the price of solving it. He cannot create such an equation and then demand of me to choose the lesser evil—i.e., to lose money so as not to commit murder. This is precisely the logic of the “pursuer” law (rodef): the pursuer who created the equation cannot claim that I should not prefer the victim’s life to his (who says the victim’s blood is redder?). That logic is relevant when the victim must kill a third party (then indeed there is “be killed rather than transgress” regarding murder), but when it is the one who created the situation, the victim has the right to demand the pursuer’s life to save his own. There we do not compare prices and prohibitions. Rights of the victim and the culpability of the pursuer override lesser-evil considerations.

An illustration: someone threatens me, “Give me a shekel or I’ll kill you.” Am I obligated to give him the shekel, or may I kill him to save my shekel? I maintain it is obvious that I may kill him—even though lesser-evil reasoning clearly says I should give the shekel. The certain loss of a shekel is surely less bad than murder. But here rights enter: I have the right to protect my property, and if someone threatens it, he cannot demand that I do lesser-evil calculus.

Incidentally, Rashi in Sanhedrin (on the Mishnah 73a) explains the permission to kill a pursuer on the grounds that by killing him I save him from the sin of murder. He seems unwilling to accept a rights-based decision; in his view, even here we act by lesser-evil calculus—if we weigh the pursuer’s life against the victim’s, what tips the scales is that by killing him we spare his transgression. Without that, it would be forbidden to kill him.[1] Rights-based considerations are thus a fourth kind of departure from lesser-evil (consequentialist) reasoning; they do not play on the outcome-comparison field.

The Trolley Problem

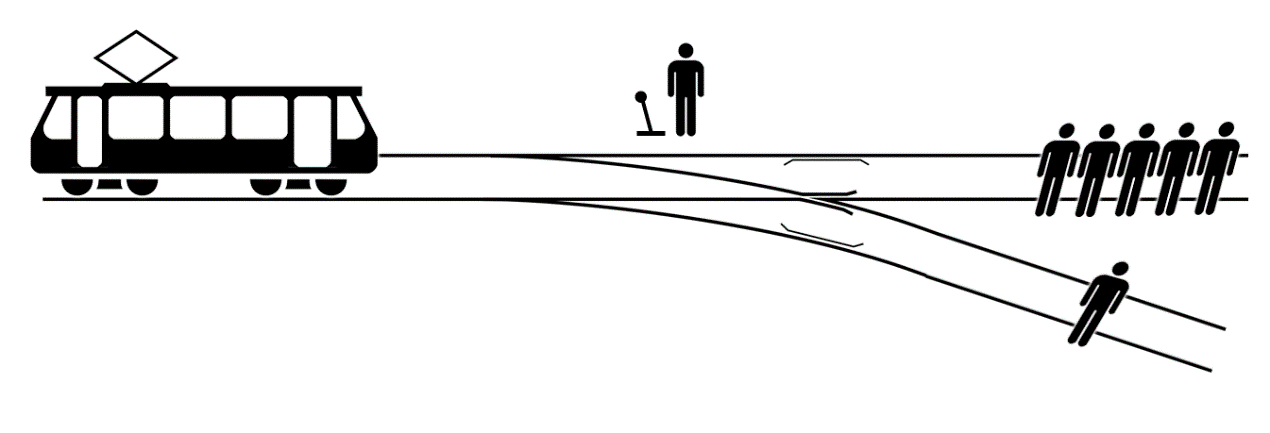

Another example linked to this discussion is the trolley problem (or the “trolley dilemma”), mentioned on this site more than once. Consider the situation depicted in the following diagram:

A train is running on the tracks toward a junction with a switch. A person standing at the junction can divert the train onto a side track. If the train continues on its current track it will run over and kill five workers on the track. On the side track there is a single person; if we divert the train it will run over and kill him. Is it permitted, required, or forbidden to divert the train?

This dilemma has been used to illustrate the debate between deontological and consequentialist ethics. In terms of outcomes it is clearly preferable to divert the train, for then only one person dies. But the one who diverts directly kills that one person by his own action. If he does not intervene, five die—but not because of him (he merely fails to save them). Consequentialists prefer diverting; deontologists can (though need not) prefer non-intervention. Again we see a present action-prohibition as against problematic outcomes without my action (“What concern have you with God’s hidden counsels?”).

It is important not to compare this to the conjoined-twins problem. There I think it is obvious we must operate, for if we do not, both will die. The meaning is that if we operate, the one who dies is someone who in any case would have died (gavra ketila), while the other will be saved. By contrast, in the trolley dilemma the person who dies instead of the five is not one of them; he would not have died but for my diversion. If the alternative were to kill only one of the five instead of all five, I think there would be full agreement to divert the train (for in that case I killed a gavra ketila).

There is a sharper variant—the trolley and the fat man. Five people are working on the tracks. On a bridge above them stands an obese man, enjoying the view. A train is approaching the five and cannot be stopped except by pushing the obese man off the bridge to halt the train. Is it right to send the obese man to his death to save the five others? The difference from the previous case is that here we directly perform a killing with our hands, whereas throwing the switch is a kind of indirect causation; but the dilemma and its sides are the same.

A Final Note: Did We Learn Anything from the Bible?

We have now reached the main point. Recall that we began with Reuben and Joseph’s rescue. In light of all the above, did we actually learn from the Bible that one ought to act by lesser-evil considerations? Did it instruct us how to act in such situations? As is known, my view is that we do not learn any values from the Bible. The value conclusions of Bible students are always the conclusions they already accepted beforehand. The game is rigged. Here, it would seem, one can decide a dilemma regarding lesser-evil considerations—so have we learned something from the Bible after all?

Obviously not. Perish the thought. Let no one suspect me that in this column we learn anything from the Bible. On the contrary: I have shown the complexity and the differences between situations, and through logical analysis arrived at certain conclusions. From this you see that our interpretation of Reuben is nourished by our a priori insights. I cannot imagine anyone who faces a situation about which he is unsure how to act and will learn from Reuben what the right course is. Usually it is the other way around: we have a view about what to do, and now we explain accordingly what Reuben did (similar or not). Ponder this well.

[1] Many have already pointed out the difficulties in this Rashi. For example, if I allow the pursuer to kill the victim, then the victim will die and afterward the court will execute the pursuer. Thus even without “saving him from sin,” there is a consequentialist argument for killing the pursuer. Perhaps, however, Rashi holds that there is no license to kill the pursuer now, due to mechanism B (“What concern have you with God’s hidden counsels?”). At present, by killing the pursuer I am transgressing, and that is forbidden; I must leave the future accounts to God. Therefore without the argument of saving him from sin there would be no permission to do so. Likewise, regarding the rebellious son (ben sorer u’moreh) we find in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 71b) that he is judged ‘on account of his end’—i.e., he is executed now to secure a future benefit—but that is a special biblical allowance.

Why do the arguments you have brought overcome the logical consideration and do not constitute part of it? After all, each of these arguments is just another interpretive way of showing that some option is actually the lesser evil (which is actually considered the greatest good).

So in fact the “least evil” approach is simply utilitarianism

You can always empty the concepts of their content and everything becomes a definition. When you compare results and act towards the less good result, you can always define that the reason you act this way is because that result is actually better. Then the investigation is basically a lie.

1- The ruling that Baran made is not similar to the principle ruling because there Shabbat is postponed and only in the beginning should one avoid desecrating Shabbat. This situation presents Shabbat desecration as an alternative only but not as an action that stands before us. Haran's argument comes to say that desecrating Shabbat is the action that is required before us and if it is fulfilled, the animal should be slaughtered.

The consideration of the lesser evil is used here only as a background player only to say that that evil is placed before us and if it is fulfilled, it is not evil.

For example, the Maggid Mishnah writes in the opinion of the Rambam that even though Shabbat is postponed according to Picun and is not permitted, in any case any action that I would have done on a weekday in the first place should also be done on Shabbat. For example, one should light a fire and not add more and more blankets to the sick person.

The recovery in this is the same - one should always do the work that stands before us for the needs of the sick person.

The opinion of those who disagree about the will is also not related to this issue.

2- It is very interesting to discuss the context of the logic that the rabbi presented in the column on the consideration of the lesser good. As it seems to me, the Radb”z believes that a prisoner in a prison who was given one prayer to pray, would pray the first prayer and not wait for a later prayer even though it cost more.

There are several other issues of lifestyle that are related to this issue. And I remember that in the past I saw poskim who were proven to disagree with it.

The recovery - the shadow of the explanation *The will – cell - the heart * that came up cell she made.

I didn't understand how this is different from what I said. The evidence you provided only demonstrates my claim that there is no real evidence for the investigation of permission or rejection. Column 404.

Indeed.

The difference is that the rabbi uses this consideration to determine that the lesser evil is not evil in the case before us. Whoever disagrees with the rabbi will pass that returning and not doing anything is preferable. And this consideration does not permit the prohibition of murder, for example. In the case of the train or the Siamese conjoined twins.

In the case of the rabbi, there is certainly a prohibition that is permitted and it is not said to return and not doing anything (in the general picture. It may be a consideration in relation to the fact that it is better for the sick person to pass through the prohibition of defilement than for us who violate the Sabbath).

In such a case, we must certainly ask ourselves which prohibition we will pass through, and there is no option left of returning and not doing anything. There, everyone will certainly ask themselves what the lesser evil is.

Rabbi, the very idea that there is a permit to commit a transgression (assuming that it is truly a permit) stems from the fact that there is really no belief that there is a true state of determinism, because what is the meaning of a permit? Only those who have a choice have a permit or a prohibition, right?

Why go so far as to permit a crime? You could say the same about any permit or prohibition. It could be argued that permit and prohibition are just rules that are intended to make us do or not do things, but do not imply choice. Determinists tend to explain things in such strange ways.

Give us one of you and we will be killed, and if not, we will kill you all” – It seems that the Jerusalemite understands that this is a categorical order, and not an order to achieve the goal that more people will live. This is also not direct, even ‘Gabra Ketul Katlit’, and it is still forbidden.

In other words, the Jerusalemite's answer to any troll problem is ‘Don't touch’. Thus

In my article on Siamese twins, I explained this Jerusalemite differently (in the conventional explanation, it is not understood. See in the book "The Bearers of the Tools" on Maimonides in the Fundamentals of the Torah). This is a law in the laws of Kiddush Hashem, and not in the laws of murder and the preservation of life. But if it is not a question of desecration and the sanctification of Hashem, then it is clear that it is permissible to hand over one in order to save the others.

In the context of your other article, I think that this (separation of twins) is again about a difference between the moral obligation not to murder, which indeed stems from the need to preserve life, and the religious obligation, which also contains halachic boundaries that you yourself spoke about in the laws of murder (restrictions in the light, etc.). The halachic rules of Grama, etc., in my opinion indicate that they do not look at the "test of the result," in a frontal conflict with morality, where every reasonable person understands that this is murder in every sense.

Agreed. I wrote it myself. Just a small correction: not only a result but also an action

Perhaps it would be worth mentioning the example you often bring up of a traditional person who asks the rabbi whether he should start keeping kashrut on the first or second of Elul (because he only keeps kashrut during the month of mercy and forgiveness) - as an example of the lesser evil considerations that are sometimes not addressed in the usual way.

True. And it seems to me that it's not just because of length considerations.