Another Look at Psychopathy and Altruism (Column 709)

With God’s help

Disclaimer: This post was translated from Hebrew using AI (ChatGPT 5 Thinking), so there may be inaccuracies or nuances lost. If something seems unclear, please refer to the Hebrew original or contact us for clarification.

In column 493 I discussed the topic of psychopathy. I noted there five planes of discussion that must be traversed in order to reach a moral and legal judgment of a person who has done something wrong (for our purposes here I will deal with an act that caused someone suffering): 1. First, the person must have a factual understanding. He must know that this act is classified as bad. 2. An intellectual understanding of the matter is also required. He must understand that the badness of an act is not a neutral definition but has binding normative meaning (not only in terms of society’s expectations but essentially). 3. An immediate experiential understanding of the concept of suffering is also required. If there is a person who, when harmed, does not himself suffer, then he lacks the understanding necessary to judge him. 4. Beyond that, empathy is required, namely the ability to step into the other’s shoes and feel his suffering. 5. Finally, control is required, meaning that the act is under his control (not something done under an irresistible impulse or unwittingly). In that column I mainly addressed the question of which of these is lacking in a psychopath.

Toward the end of that column I touched on the matter of the psychiatric opinion (discussed in my article here), i.e., to what extent a psychiatrist can truly determine a psychopath’s condition (namely, answer those five questions above), and in doing so I also mentioned the question of the relationship between brain and mind. I explained that in a materialist view all these discussions lose their meaning. According to such a view, a person is no more than a reflection of his brain, and none of his actions are under his control (in the sense that he could have acted otherwise). His responses are products of external stimuli and brain processes that are not in his hands, and therefore, in principle, one could observe the brain and extract from it answers to all five questions (at least in principle; today we still lack all the knowledge and instruments). In such a materialist picture there is no fundamental difference between a normative person and a person with a psychopathic brain, apart from the brain structure they possess. A different brain structure is certainly not grounds for assigning responsibility and judging a person morally and legally. I explained that there is some sense in punishing him in order to correct his brain (that is, to cause him to act differently next time), but here I am not dealing with judgment in the sense of imposing punishment, rather with the question of responsibility (moral and legal).

I recently came across an article in National Geographic (Hebrew edition, January 2018, issue 236, p. 52) that deals with psychopathy, and in particular the link between it and brain structure. I saw there several points worth discussing and thought to devote this column to them.

Opening: Altruism and Psychopathy

The article opens with a set of images of several cases (all in the U.S., the world’s psychopathy capital) of senseless mass murder of people in schools, clubs, a music festival, or just on the street. Then an impressive set of serial killers is added to the list. The written portion of the article opens with an event of extreme altruism. A mother of two saw a disabled man in a wheelchair stuck on a train track. He cried out for help, and the vehicles passing by did not stop or approach him. She immediately left her two children (asking someone to watch them) and ran to him, struggling to free him from the chair as the train approached at 125 kph. She did not succeed, but did not give up, and at the last moment managed to fall with him off the track to the side, and the train smashed the chair that remained in place and dragged its parts along. The writer (or translator) places alongside this side of the equation the case of Roy Klein and the like.

These cases illustrate, in the extreme, two of our fundamental tendencies: extreme altruism (self-sacrifice, generosity) and psychopathy (cruelty, egoism, destructive impulses). These opposing tendencies are found in many people in varying degrees, and these cases are of course extreme manifestations of them. It is commonly thought that the source of both tendencies is evolutionary, since survival sometimes demands cruelty and sometimes cooperation, devotion, and sacrifice (the sacrifice is usually for the survival of the species/gene and not of the sacrificer himself).

The Brain’s Contribution

In the last generation the focus of the discussion has moved from genome and environment to the brain, and from philosophy and religion to science, and within science from evolution to the brain. The root of the tension between these two tendencies, as well as between good and evil in general, is the emotional trait called “empathy.” Yet in the standard picture of neuroscience, emotional traits reflect different brain structures. Empathy is no exception, and it too is governed by our brain.

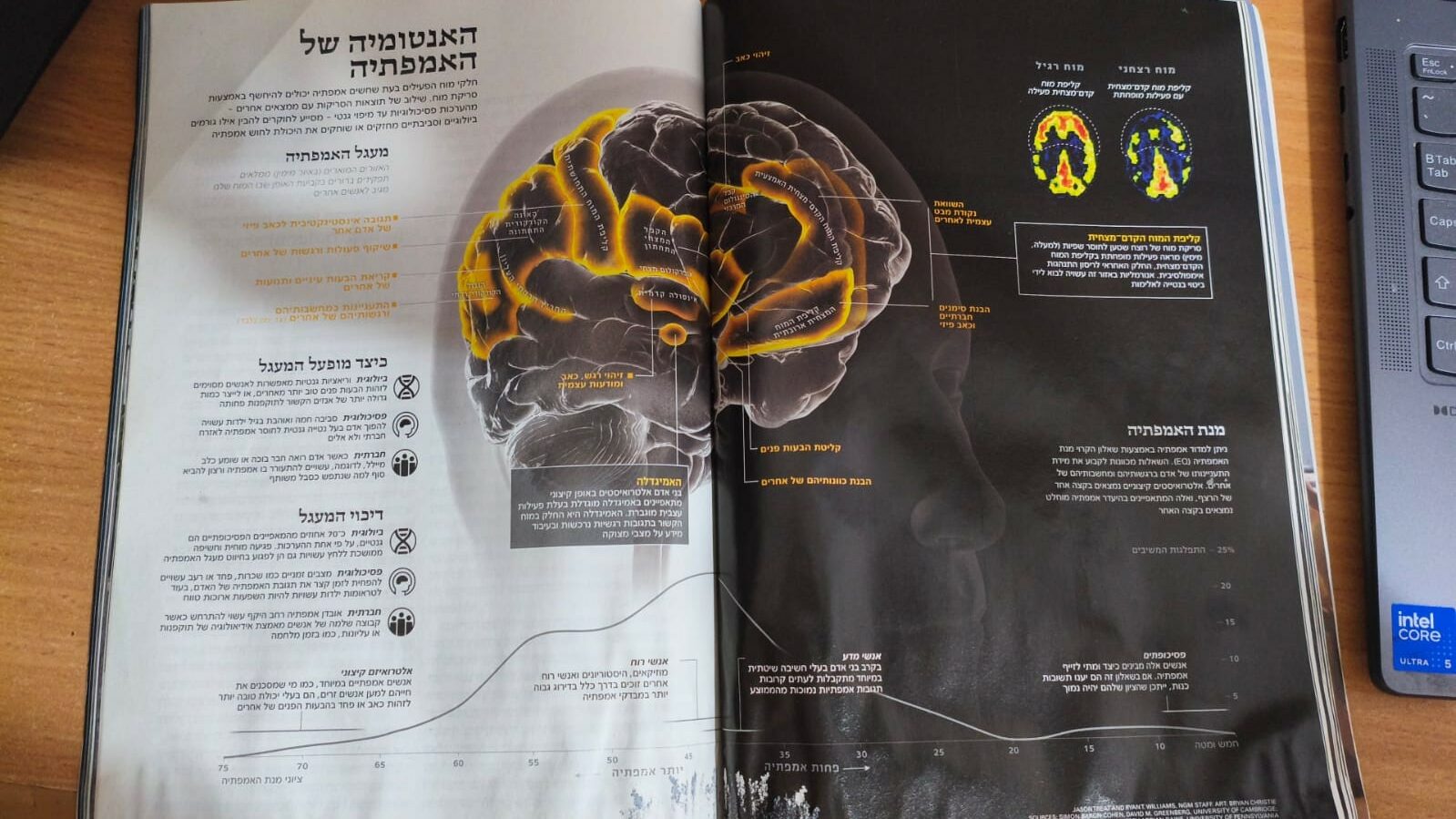

The article presents the following schematic description of brain influences on empathy:

I will briefly describe the matter.

Empathy quotient (EQ) is usually measured in different ways via questionnaires, and the result describes the extent to which a person is interested in and understands the emotions and thoughts of others. Extreme altruists have a high EQ and psychopaths have a low EQ. However, many psychopaths understand how to fake empathy, and therefore verbal questions will not reveal their psychopathy (they will answer as expected). By contrast, observing the brain can give us a better diagnosis.

Brain scans of various people (some psychopaths) have given researchers a better understanding of this phenomenon. In the diagram you can see that different parts of the brain are responsible for functions that contribute to empathy: understanding social cues and facial expressions (including pain), understanding others’ intentions, comparing a self-perspective to others, and more.

In general, the difference lies mainly (though not only) in two places in the brain: the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for restraining impulsive behavior, and the amygdala, which processes information about distress states and emotional responses. When activity in the prefrontal cortex is reduced—restraint is low, and impulsivity increases (which leans toward the psychopathic), and vice versa. By contrast, high activity in the amygdala reflects altruism.

From here one can infer which environmental and biological factors raise or lower empathy. Psychopathy is a combination of three types of influences: psychological (temporary states of drunkenness or hunger, childhood trauma, etc.), genetic (which govern the structure and activity of those brain areas), and social (for example when a group adopts an aggressive and violent ideology, or during war). That is, there is a contribution from a person’s brain structure, but also external influences that change the level of activity in each such brain part. In the end, the brain activity generated by these two kinds of factors determines the level of psychopathy.

This picture essentially tells us that altruistic behavior is the result of an ability to better identify others’ facial expressions and emotions, and of course also to identify with their pain, suffering, and fear. Psychopathy is the opposite state. Up to this point you can see that the description is quite similar to what I presented in column 493, except that here there is an added element: in this article it seems that all this is tied to brain activity. That is, beyond the psychological description of the five conditions for psychopathy, here we discover that those five conditions themselves are not the fundamental matter. They too are but expressions of brain structures and brain activity. Psychopathy is the result of faulty neural circuits that lead to a lack of empathy.

Empathy in Children

In the past, researchers believed that children cannot relate to others’ mental states, but recent findings reveal that very young infants already feel empathy. When infants a few months old were shown situations of a person suffering, in pain, or insulted, they responded with movements indicating empathy (an attempt to approach the person and make contact, even a hug or a kiss, or giving a toy to a crying child).

But there is a minority of children who do not show such signs of empathy. Some researchers report that from their second year of life onward, there are children who tend not to display empathy. To a child who fell they announce that it did not hurt. They laugh at him and do not share in his sorrow. Tracking the maturation of such children has shown that they have a higher likelihood of developing antisocial and delinquent behavior. So too for teenagers who showed lack of sensitivity and emotional expression, violent and aggressive behavior, such as extreme aggression and vandalism. They too have a higher likelihood of developing callousness and cruelty that lead them to commit cruel acts with alienation and callousness. Such youths may develop psychopathy in adulthood.

Does this mean that psychopathy is innate? The result of brain structure (defects in empathy circuits)? Not necessarily. It seems there is an influence of brain structure, but that is nothing new. But it does not mean that this is all there is. The wording in the article itself hints that it is not deterministic. There are those who showed such behaviors in childhood and adolescence who did not become psychopaths in adulthood (the article speaks of increased likelihood of becoming psychopaths). Moreover, no data are cited on the reverse cases: ordinary children and teenagers who became psychopaths as adults. Why does this matter? Because if such cases exist, that could indicate influences beyond the innate ones.

Immediately afterwards, the writer himself raises the possibility that beyond genetics there are also hereditary (how is that different from genetics?) and environmental influences. The indication for this is studies on twins and on children born to parents with antisocial behaviors who grew up in normative families—some that provided warmth and a warm and supportive emotional environment, and some that did not. Unsurprisingly, it turns out that environment also affects psychopathic behavior and emotional regulation.

Between Understanding and Feeling

Various researchers claim that psychopaths can think about and understand good and evil, but not feel it (or feel it less). Many of them mimic emotional and empathetic behaviors expected in such situations. Thus, for example, in the city of Derby in Britain in 2012, a house burned down with six siblings inside. Only one survived. Residents collected money to support the family, and the parents thanked them warmly on television and even cried there out of emotion. Mysteriously, the handkerchief with which the father wiped his eyes remained dry. In time, the parents were convicted of deliberately causing the fire in order to incriminate the father’s mistress. From similar cases one can gather that psychopaths understand what is expected of them and can distinguish between good and evil, and of course also know the behavior required in such situations, but do not truly feel it. There are claims that because of a lack of gray matter in the amygdala, the psychopath’s emotional activity is greatly reduced, and he compensates for this using other brain areas—except that these do not arouse emotions in him, but rather thought that performs a cognitive simulation of what is happening in the realm of emotion.

Altruistic Kidney Donation

Abigail Marsh studied altruistic kidney donors who received no compensation and sometimes even bore the costs of the donation. She scanned their brains when they were shown fearful, angry, or neutral facial expressions. It emerged that they have a higher-than-average amygdala response compared to the control group, to fearful faces. In fact, their amygdalae were also larger than those of the control group. By contrast, psychopaths’ amygdalae were smaller than average. In other words, a brain influence on the degree of empathy in people (across the spectrum from psychopathy to altruism) is demonstrated here.

Again, clearly there are environmental influences on altruistic acts such as kidney donation, but clear brain findings underlying these phenomena were also found. This reminds me of a question that came up in the site’s Q&A a few days ago, where the questioner wondered what I make of the fact that an overwhelming majority (87%) of kidney donors in Israel are religious. I said I don’t learn much from this, since there can be many factors. I will elaborate a bit more here. It is unlikely that there is a difference in brain structure between the groups (though it is possible that religious people on average have different brains, and if that difference accounts both for religious belief and for altruism). It is more likely that something in their environment made the difference. This actually strengthens the claim that there is something better about them (since a different brain structure does not form a basis for a judgment of good or evil. Good or evil is tied to people’s choices). It could be education, religious commitment itself, and more. Does that mean they are better? I am not sure.

Religious commitment is not necessarily tied to goodness. A person who does such an act because it is God’s will is not necessarily a better person. He is a more religious person. He may also do it to receive reward in the world to come, in which case it is even less clear whether we can regard it as good. Moreover, the very belief in the world to come can raise the likelihood of altruistic donation, since these are people who know that this world is not the whole picture, and death is not the end of the line. Beyond this, there are likely environmental and cultural influences, since the religious society encourages such donations, and apparently also offers practical support to donors and their families. Such factors may indicate good conduct by the religious society, but not necessarily the goodness of the individuals (just as the scandalous and immoral conduct of the Haredi society does not necessarily testify to the evil of the individuals within it). I mentioned there that there are altruistic activities that characterize secular people in particular, and you will find almost no religious people there—activities such as Greenpeace on behalf of the environment, the earth and climate, aid delegations to disaster victims around the world, and the like. These actions are done mainly by secular people. And even regarding kidney donation, there are many more religious-Zionists than Haredim, so again there is no clear effect of religiosity as such.

Collective Evil

We spoke about collective good and evil, and the article also devotes a section to collective evil, such as war, or mass-murder events (the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, ISIS in the Yazidi massacre, the Hutu who massacred the Tutsi in Rwanda, the Nazis, and more). It is very hard to attribute such events to brain structures, since we are talking about large groups and it is likely that the distribution of brain structures there is like that in any other large group. It also targets specific people rather than indiscriminately any other. Therefore, there it seems like environmental and cultural influence—submission to authorities, ideological brainwashing, nationalism and religiosity, and more.

Within these processes, it is customary to define the other group as “different” or “other,” and from there also inferior and more evil, plotting against us such that we must constrain them and even kill them. In the first stage one moves to discrimination and reduces empathy toward them. Those who speak up for them are considered traitors or enemies, and in the end it concludes with a mass, indiscriminate slaughter. Those who participate in such slaughter feel no remorse because they have an explanation and justification for it.

This is another demonstration of environmental influence on psychopathic behavior. This means there are ways to reduce psychopathic behaviors or increase altruism. As we saw above, warm, supportive families or educational frameworks improve the situation and sometimes offset brain and genetic influences. There are studies that have shown this also regarding compassion training and various meditations, done deliberately.

Different Motivations in the Moral Arena

The article mentions that kidney donors report that they receive compensation in the form of feeling good and satisfaction from the very fact that they donated. This feeling naturally depends on brain structure (such as amygdala size, and so on). Does such a feeling mean they are better people? One can broaden the discussion and claim that any such decision always occurs within a confrontation between two kinds of considerations: fear of the consequences (pain, health cost, etc.) versus benefiting the other. When there is a group with more donors, this can be explained in at least two ways: either in that group fear is smaller (for example from belief in the soul’s survival), or that the desire to donate is greater (and that too perhaps due to reward in the world to come, or social incentives). Both sides may depend on brain structure and innate data, and also on environmental factors. But if anything, only the second explanation can form a basis for a claim of moral superiority of that group. Lack of fear, regardless of its reasons, does not raise one’s moral standing.

Sometimes altruism is expressed in an action that reacts quickly and offers help to a person in distress. For example, a person who saw a policeman under fire and stopped by with his car and evacuated him, or a doctor who risks his life under fire to save people he doesn’t know, a person who rescues victims under fire (as in the Nova events), and so on. Such actions also depend on capabilities such as quick reaction, resourcefulness and initiative, physical strength, fitness, and not necessarily on moral goodness.

All the motivations I described here and similar ones influence altruistic acts, but it is hard to see in them a moral matter. People who act from these motivations are not more moral than others. This means that we cannot judge a person by his deeds. It is not the deeds that determine whether he is an altruist or a psychopath, but the motives.

On Behavior and Moral Judgment: The Meaning of Free Will

More than once I have pointed out the common mistake of linking empathy with morality. The moment you offer a mechanical, evolutionary, or brain-based explanation for altruistic behavior, you have turned it into mechanical behavior and therefore into something not morally justiciable. Such behavior—better or worse—has no moral value; that is, one who acts thus cannot be considered a moral or anti-moral being. The same holds for the influence of emotion on our behavior. Emotion and empathy indeed influence our behavior, but it is not correct to identify them with our morality. Assuming that Reuven acts in a more altruistic way than Shimon due to differences in their emotions or brain structures, it is not correct to say that he is more moral than Shimon. So too regarding psychopathic actions arising from such causes.

This means that the entire analysis I have described so far, like many studies in neuroscience and psychology, suffers from a serious logical fallacy. They analyze a person’s behavior through the various motivators (brain, genetics, evolution, emotions, socialization, environment), and the whole discussion is only about the relationship between these motivators and one another—which is dominant and which is less so. In short: the nature or nurture question. But such an analysis has a double problem: 1. It empties these terms of ethical judgment. 2. It ignores choice and free will.

- Psychology vs. Judgment

If indeed nature and nurture are the only kinds of causes/influences that govern our behavior, then there is no room for ethical judgment. Note: this is true for both nature and nurture. In the analysis presented so far, speaking of a person as an altruist or psychopath is a description of modes of conduct, not judgments about the person himself. In other words, the characterizations of altruism and psychopathy belong to the realm of psychology, not ethics. This is of course not a fallacy but merely a clarification that it is important to be aware of. One can say that indeed a person is a product of nature and nurture and nothing more, and then there is no point in dealing with judgments and the moral plane at all. But it is not correct to see a person that way and still continue to judge him and evaluate him morally.

- The Meaning of Free Will

At least for me, as a libertarian, the analysis presented so far also has a factual problem, namely a problem in the analysis itself. It ignores another central factor: our free will (choice). Our will can operate on top of all the data described so far and decide whether to go with them or against them. A libertarian holds that a person with a given brain structure can still decide whether to yield to the directions into which his brain structure pushes him or to resist them. The same applies to environmental influences. This means that our decisions are made by the internal circumstances (nature) and the external ones (nurture), on top of which there is another level of decision by the person. The circumstances form a framework for our activity, not a complete explanation of it. In such a picture, the terms altruist or psychopath describe a person’s tendencies but not his actions. What he will actually do is not dictated by those tendencies, but at most influenced by them.

In columns 175, 173, and in the articles here and here, I described this worldview using a model that views all these influences as some topographical map within which the person operates. This topography describes the totality of influences on us, and the person who acts within it is influenced by all of them. For example, if someone provokes him, he has several possible reactions: ignore; respond with violence; rebuke the offender; complain about him. The influences of genetics and environment acting on him create different slopes around him in these directions. For example, if he is a violent person, there will be a steep slope toward the violent response and a high mountain toward restraint. It will be hard for him to restrain himself and very easy to respond violently. This topographical contour tries to make the person go in certain directions and to prevent him from going in others. But after all this, the person can nevertheless decide to climb the mountain, i.e., to do something his natural tendency rejects (the neurologist Benjamin Libet called this “vetoing.” See more in column 128 and the article this and this, and much more). The topography does not determine what we will do but only influences it. In the end, a person can decide to climb a mountain or refrain from sliding down a slope, despite all the influences. A small ball rolling on this topographical surface cannot do that; it will necessarily move in the direction into which the topography pushes it. This is the meaning of a person’s free will in contrast to an inanimate object.

At the beginning of my book Science of Freedom, I pointed out that many researchers are confused and claim that environment is what saves our morality. In their view, if our actions were products of innate brain influences, then indeed we could not speak of morality and moral judgment. But since there is brain plasticity, rooted in the possibility of educating and influencing it (and through it us) by environmental and cultural tools, these influences are what make us moral beings (and not robots). But that is a mistake. Environmental influences are no different from genetic and brain influences. There is no difference between a plastic brain and a fossilized, rigid one. As long as my actions are products of influences—internal (nature) or external (nurture)—my actions have no moral meaning, and there is no room to judge me for them. Moral judgment exists only if these are actions I freely chose to do. Circumstances and influences (the topographical contour) can at most be arguments regarding punishment.

Interim Summary

One can of course espouse determinism or materialism, within which there is no place for free will and free decisions. Such a person will naturally hold that our actions are products of the variety of influences described above. In my view as a libertarian this is perhaps an error, but it is not a fallacy. That is not what I meant above when I spoke of a fallacy—that was the clarification in item 1 above. The fallacy is that if one indeed holds such a view, one should not speak of morality and moral judgment. In his worldview, altruism and psychopathy are descriptions of behaviors or different human types, not judgments. In other words, both are concepts from the semantic field of psychology, not ethics.

In column 646 I noted that a determinist can explain why we need to judge people and even punish criminals, but pointed out there that this is not moral judgment but sanctions imposed to achieve certain outcomes—correction of the person and society. Moral judgment (i.e., concepts like good or evil) cannot exist in a materialist-determinist conceptual world. See there all the semantic contortions and forced dialectics that materialism and determinism impose on their adherents.

Further Clarification: On Emotion and Morality

Now think of a person who is not endowed with empathy. When he sees the pain or suffering of others it does not affect him in any way. His emotions do not respond to this, whether it is the result of nature or of nurture. Such a person is defined as a psychopath in neuronal terms, since he lacks empathy for others. But according to what I have said, he can still behave morally if he chooses to overcome his impulses or to act according to his intellectual understanding even without having emotional drives to do so. Such a person can understand intellectually that the other is suffering, even if he has no empathetic feeling toward him (that is, he does not experience the suffering of the other—he only understands it with his mind), and act accordingly. Is there anything lacking in the morality of such a person? In my eyes, absolutely not. On the contrary, in my eyes this is the most moral person, since he acts from pure moral reasoning and not because his “gut feelings” (emotions) push him to act. See on this in column 22 (in particular the example from A Beautiful Mind regarding John Nash) and in columns 259, 311 – 315, 371, and more.

Incidentally, the common assumption is that, whether nature or nurture, ultimately what produces our behaviors and feelings is the brain (the nature-nurture issue touches only on why our brain is built and functions as it does—whether it is innate or acquired). If a person decides to overcome his initial tendency (which is generated by the brain) or to go along with it, I am not sure whether that choice will also be reflected in the brain. That is, whether that action will fail to match the brain’s dictates (the choice goes against that dictate) or whether the choice itself also affects brain activity—so that in the end what I do will always match the brain’s dictates. Of course, even if choice affects the brain, it can happen long before the very moment of choice (a person who chooses to be good thereby changes his brain structure), and it can also occur at the moment of choice (in which case brain structure does not change, but momentary activity can). In any case, in the long term many such momentary choices will likely also affect brain structure and the tendency to do good in future cases. This is an interesting neuronal sense of the dictum of the author of Sefer HaChinuch, “After the deeds, hearts are drawn.”

We have seen that a person devoid of empathy in the emotional-experiential sense can still act altruistically, and conversely: a person with an altruistic brain structure can choose to act badly. That is, it is not correct to identify emotion and brain structure with morality. The terms altruism and psychopathy can belong to the brain world (the psychological-neuronal), but then we should not use them as judgments. This, however, raises a practical question: can such a state occur in practice? If a person has no emotional response to another’s suffering and distress, why would he nevertheless choose to help him? He does not grasp that the other is suffering, so what would move him to help?!

Above I explained that such a person understands intellectually that the other is in a state of suffering, but he has no immediate experience of what such a state is. He does not experience what people feel in such a state. To proceed, we must distinguish here between the different states I described in column 493, in particular between these two: 1. States in which a person knows intellectually that the other is suffering but does not understand what suffering is (he himself does not experience states of suffering even for himself). 2. States in which a person experiences states of suffering in himself, but has no empathy to feel the suffering of others. In such a state he can understand that the other is suffering and also understand what that means, but he lacks the emotional drive to act to ease the other’s suffering.

In states of type 1, one can imagine a wholly moral person who will not act because he lacks the information by which he understands that he must act. This is essentially a kind of blindness, and therefore one should not see it as a moral flaw. Such blindness is not related to the person’s morality, for if he understood that he should act he would indeed act. Think of a blind person who does not see the pauper standing before him and therefore does not give him charity. Is it correct to say of him that he is morally indifferent or not altruistic? On the assumption that if he had seen him he would have given him charity, then this is a moral and good person; it is just that his blindness prevents him from receiving relevant data, and therefore he does not act thus in practice. That is exactly the state in a person who is psychopathic on the emotional plane. Therefore it is not correct to identify that with lack of morality.

By contrast, in states of type 2, the person knows all he needs to know. He lacks no data, but he has no emotional drive to act. In such a case I would expect a moral person to act even if he has no empathetic feelings. He will choose to do so coldly, without an emotional push to do so. In the columns above I illustrated this with John Nash, who experienced (imaginary) people chasing him and taught himself to ignore them and behave as if they did not exist. His intellect took control over his sensations and emotions (even though they had a visual manifestation in his imagination). Another example is that of Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor, a neurologist and brain researcher, who herself suffered a stroke that damaged the left hemisphere of her brain. She describes, with full awareness, her experiences and the nature of her perception in this state, and how she taught herself to act correctly even without the emotional drives that exist in ordinary people. See her TED talk here.

Above we saw that psychopaths understand how a person is supposed to behave when another is suffering but are indifferent to it (and merely present a façade of empathy). From similar cases we can learn that the understanding of how it is right to act apparently exists in them, and what differentiates them from Jill Bolte Taylor is the willingness to act without emotional drives (though it is possible that they merely know that this is how people actually act, but do not understand that this is how one ought to act. Such a state is similar to type 1, since it is a kind of blindness). It is precisely this willingness that is decisive for moral judgment, but the question whether there are or are not emotional drives of empathy is not related to the moral plane but to the question of blindness. Empathy is perhaps a condition for moral behavior (it provides the data that enables a moral person to act), but it itself stems from brain structure (innate or acquired), and therefore in itself it has no moral meaning. As noted above, it is not even a necessary condition, since people can act morally even without empathetic feelings, solely out of their moral understanding without emotional motivation. And conversely, people with empathetic feelings can act immorally and harm others (after all, not every criminal is a psychopath).

This means that the moral question concerns only the top rung of the five-step ladder I outlined in that column: our choice and control over our actions. All the rest are at most conditions for moral behavior, and usually not even that. The identification of emotion with morality is conceptually mistaken (and I have often noted that it is even destructive and harmful).

I will conclude the column by responding to a question that came up in the Q&A a few days ago.

The Connection Between Brain, Behavior, and Morality

David wonders there:

How does the rabbi relate to cases where damage to the brain (for example, severing the two hemispheres) causes a change in a person’s personality—for instance, someone whose connection between the two hemispheres was severed and he began to have two different personalities, etc.? In terms of the soul.

In the latter part of my book Science of Freedom I addressed these questions at length. Here I will address it briefly, just to complete the picture.

A change in brain structure changes the topography within which a person operates. This can create tendencies different from those he had previously. But as we have seen, tendencies do not determine our judgment of him. What matters for that is the decisions that person makes (whether to go with his tendencies or to resist them—to veto them). As a dualist who holds that the soul is responsible for our choices, I would answer David that the soul is influenced by the brain and the tendencies it induces, but is not determined by them. Therefore it is no wonder that a brain change changes personality. Certainly a person’s feelings and tendencies change, but it is still the same person with the same soul. It is important to understand that I fully agree that after the change his choices will be different, but that does not mean he lacks a soul or that his soul has changed. The soul operates within the topography set by the body (the brain). The product is the final act that is done, and it is a combination of the two. The very same eyes will see the world in red if we place red cellophane over them, and in green if we place green cellophane. The different data a person receives, and the different tendencies with which he contends, can certainly lead to different behavior. But they influence behavior; they do not determine it. The same person (that is, the same soul) will act differently if the topography within which he operates is different.

An extreme case I discuss in my book is a person whose two brain hemispheres were separated, and it turned out that each had a different worldview. One was Republican and the other Democratic. From time to time claims arise that prove from this that a person has no soul and that everything is a product of the brain. But this is a mistake. Each hemisphere is responsible for processing the arguments for one side. The person is supposed to weigh all these arguments and reach a bottom line. This processing and weighing will take place only if there is a connection between the two parts of the brain. If there is no connection, then the same soul is expressed in two forms separately. Its Republican part is represented in hemisphere A and its Democratic part in hemisphere B. But this is a split in the practical expressions of our soul and not in the soul itself. And of course it does not prove that we do not have a soul. I likened it there to a prism that separates white light into the full spectrum of colors from red to violet. All the colors were within the white light, but the prism split them and presents them each separately. This is not the place to elaborate further.

Discover more from הרב מיכאל אברהם

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

If when you split the brain you get two different people at the same time.

That means there is no soul at all because otherwise how would it not know about the split in question…

Who said she doesn't know? It's not in the actual expression of the soul because the expression of the soul is only through the brain.

But the soul is the person who experiences, isn't it?

Chinese

In light of your words, can an ethical value judgment be attributed to any person (good or bad) as a whole as his personality (a kind of current potential state), or does such a judgment actually mean only that that person has tended in the past in most cases to choose good (with a moral motive) even if topographically he had to climb mountains (or in the direction of evil in the opposite case) and that perhaps future choices can be deduced from this as well?

My intuition is that there are good and bad people as a current personal status and not just a historical description of their choices, but I'm not sure how that fits with the picture you've presented.

A fascinating question. I hadn't thought about that. On the surface, it seems that one can only judge an act and not a person in general. A person's tendency to be good is a tendency and not a choice, and therefore is not subject to judgment. It also does not make him choose good, but only influences him in that direction. But our tendencies are also the result of our past actions (hearts are drawn to actions). So perhaps there is room to talk about a judgment of a general personality. Beyond that, a person who chooses good does not necessarily do so every moment. There are fundamental choices that are realized in every case over and over again. If a person chose good in general, then he is a good person. This will be reflected in most of his actions (although not always). It is somewhat reminiscent of the distinction you made between two types of answer: https://www.google.com/url?client=internal-element-cse&cx=f18e4f052adde49eb&q=https://mikyab.net/%25D7%259B%25D7%25AA%25D7%2591%25D7%2599%25D7%259D/%25D7%259E%25D7%2590%25D7%259E%25D7%25A8%25D7%2599%25D7%259D/%25D7%25A2%25D7%259C-%25D7%2594%25D7%25AA%25D7%25A9%2 5D7%2595%25D7%2591%25D7%2594-%25D7%2591%25D7%2599%25D7%259F-%25D7%25 98%25D7%259B%25D7%25A0%25D7%2599%25D7%25A7%25D7%2594-%25D7%259C%25D7 %259E%25D7%2594%25D7%2595%25D7%25AA/&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwi4jaay7I-NAxV3BfsDHTGSETcQFnoECAcQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2dlW_BBwI5LNdqRET3u4KQ

Miki,

How can one “understand intellectually that another is in a state of suffering”?

cautiously.

Do you understand the pain of others intellectually and not feel it emotionally?

Not me. I feel it too. But there are people for whom this is probably the case.

The prohibition against gossip differs from the prohibition against slander in that the narrator is not an objective bad story about the other person but a subjective bad story. The prohibition is to gossip about the other or, in the words of Maimonides, spy on the other. And here the question arises: is the main thing that you know that the narrator is careful and therefore will not tell things that he does not want to be told, or that you feel that such things are not talked about and the narrator is just an example of this? In other words, is it a psychopathic commandment (the narrator is careful and therefore does not tell), or an empathetic commandment (such things are not told and the narrator should know this, but then it does not belong in a psychopath since he does not have empathy)?

The connection is very tenuous. I think both are correct.

Regarding the case of the split brain. What is strange in this case is that the soul is not supposed to be divided into two even if the brain is divided. That is, that soul is supposed to be connected to both parts of the brain and thus somehow mediate between them. At least there should be some awareness of that soul that it can think through two different parts of the brain. And if so, why didn't that soul try to reach a decision on the question of democracies versus republicans? After all, it is the soul that is supposed to ultimately decide such questions of value.

The soul may formulate one position, but it cannot be expressed in our world because its expression is through the physical mediators (the brain).

Asked differently, is the soul the ”I”?

Does the same person have one “I” or two?

I don't know the answer. I'm just proposing a model according to which this phenomenon does not refute dualism. The model is that of a prism, which splits the shades that were in the original beam. The soul can also contain all the arguments with different weights so that there is a decision. But its expression in our world is done through the brain, and in the split brain each of the two parts processes the type of considerations that belong to it (that is, that are transferred to it from the soul). Therefore, two personalities are created here.

I remember you often saying that we think with our brains like we walk with our feet. That is, there should be three stages here, like in a computer: input, processing, and output. Assuming that the processing is done in the non-material part of us (the spirit or soul), it is what should dictate the output according to the processing done. Maybe you mean that there are two stages of processing, one on the spiritual side and the other on the material side, and because the processing on the material side is different, there is a different output?

This is not contradictory. The soul thinks through the brain, and processes both types of considerations in both parts of it. The synthesis between them, even if it is done in the soul, cannot be expressed in our world when the brain is divided.

I got another famous example from GPT on this matter:

When a split-brained person was asked if he was religious, one side answered “yes” and the other side “no”.

I assume that this is a factual assessment of the person (whether or not there is a God). Do you think that in this situation too the behavior can be explained with the prism model?

A more familiar example is that the left side was Democratic and the right side Republican (I think for and against Nixon). It's the same thing.

There are considerations here and there and they are expressed in both hemispheres.

By the way, regarding what you wrote here:

She describes with full awareness her experiences and the nature of her perception in this situation, and how she taught herself to act correctly even without the emotional impulses that exist in ordinary people.

I saw Jill Bolty Taylor's TED talk and I didn't see her talking there about losing emotional impulses at all. Did you hear that anywhere else?

I saw it many years ago. I don't remember.